With over 38.4 million Americans living with diabetes, finding effective tools for blood sugar management is more critical than ever. Among the many strategies available, understanding one particular concept can fundamentally change how you approach your diet.

The glycemic index (GI) is a scale from 0 to 100 that ranks carbohydrate-containing foods by how quickly and how much they raise blood glucose levels after eating.

For individuals managing diabetes, mastering this concept is not just academic—it’s a practical pathway to achieving more stable blood sugar, reducing the risk of long-term complications, and gaining a greater sense of control over their health.

This guide goes beyond a simple definition.

You will learn the crucial difference between glycemic index and glycemic load, how to use a glycemic index chart to build healthy meals, and discover practical strategies backed by the latest scientific research to improve your diabetes management.

Let’s explore how this powerful tool can transform your approach to eating.

In This Article

Part 1: What Is the Glycemic Index (GI)? The Core Concepts

Before we can apply the glycemic index to diabetes management, we must first build a solid foundation.

This section breaks down the core principles of the GI into simple, understandable concepts, setting the stage for the more advanced analysis that follows.

Defining the Glycemic Index: A 0-100 Ranking System

At its heart, the glycemic index is a measure of carbohydrate quality, not quantity.

Think of it as a “speed rating” for how quickly a specific food containing carbohydrates is digested, absorbed, and converted into glucose in your bloodstream.

Foods are assigned a numerical value on a scale of 0 to 100.

The benchmark for this scale is pure glucose, which is given a GI value of 100.

All other foods are ranked relative to this standard.

A food with a high GI value causes a rapid and significant increase in blood glucose, while a food with a low GI value results in a slower, more gradual rise.

It’s crucial to understand that the GI applies only to foods containing carbohydrates. Foods that are primarily protein or fat, such as meat, fish, poultry, and oils, do not have a GI value because they have a negligible effect on blood glucose levels.

Understanding the GI Scale: Low, Medium, and High

The GI scale is typically divided into three categories. Knowing these ranges is the first step toward making informed food choices.

This classification provides a simple framework for identifying which foods will likely support stable blood sugar and which may cause unwanted spikes.

- Low GI: 55 or less

These foods are digested and absorbed slowly, leading to a gradual, steady release of glucose into the bloodstream. They are the cornerstone of a low-GI diet and are generally preferred for diabetes management. Examples include most fruits and vegetables, legumes, whole grains like barley, and minimally processed foods. - Medium GI: 56-69

These foods have a moderate impact on blood sugar levels. They can be included in a balanced diet but should be consumed with attention to portion size. Examples include sweet corn, bananas, and some types of bread and breakfast cereals. - High GI: 70 or more

These foods are rapidly digested and absorbed, causing a quick and sharp spike in blood glucose levels. For individuals with diabetes, these foods should be limited or carefully paired with low-GI foods to mitigate their impact. Examples include white bread, white rice, potatoes, and sugary snacks.

How Is a Food’s GI Value Determined?

The GI value of a food is not an arbitrary number, it’s determined through a standardized scientific process.

This method ensures that the values are consistent and comparable across different studies and food databases.

As outlined by institutions like the Mayo Clinic, the process generally involves these steps:

- Participant Group: A group of at least 10 healthy volunteers is recruited.

- Reference Food Test: On one day, after an overnight fast, each participant consumes a test portion of a reference food (either pure glucose or white bread) containing exactly 50 grams of available carbohydrates.

- Blood Glucose Monitoring: Their blood glucose levels are measured at regular intervals over the next two hours to plot a blood sugar response curve.

- Test Food Test: On a separate day, the same process is repeated, but this time the participants consume a portion of the test food (e.g., an apple, a slice of bread) that also contains 50 grams of available carbohydrates.

- Calculation: The GI value is calculated by comparing the area under the two-hour blood glucose response curve for the test food to the area under the curve for the reference food. The result is expressed as a percentage, which becomes the food’s GI value.

This rigorous testing, conducted by research bodies like the Sydney University Glycemic Index Research Service (SUGiRS), provides the authoritative data that populates the international GI database.

Part 2: Why the Glycemic Index is a Critical Tool for Diabetes Management

For the general population, the glycemic index is a useful concept for healthy eating.

For individuals with diabetes, however, it is a critical tool for daily management and long-term health.

This section delves into the physiological mechanisms and scientific evidence that underscore the importance of the GI in controlling diabetes.

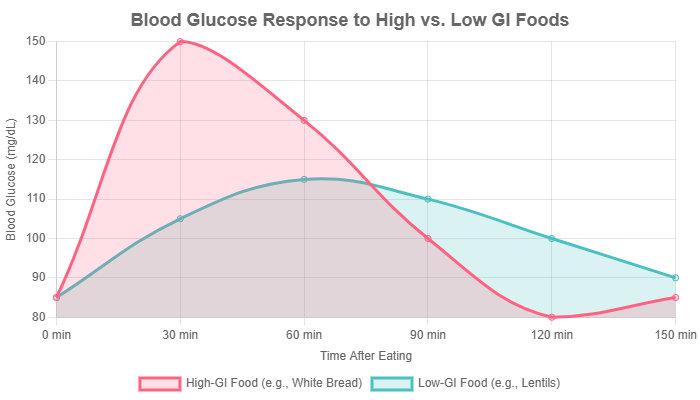

The Physiological Impact: Blood Sugar Spikes vs. Stable Energy

The core challenge in diabetes is managing blood glucose levels.

The body’s ability to produce or effectively use insulin—the hormone that moves glucose from the blood into cells for energy—is impaired.

This is where the GI of a food becomes profoundly important.

When a person with diabetes consumes a high-GI food, the rapid influx of glucose into the bloodstream creates a significant challenge.

The body must mount a large, fast insulin response to handle this surge.

In type 2 diabetes, where insulin resistance is common, the cells don’t respond well to insulin, leaving glucose to linger in the blood.

In type 1 diabetes, this requires a precisely timed and dosed bolus of insulin, which can be difficult to match perfectly, often leading to post-meal hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) followed by potential hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) as the insulin eventually overcorrects.

In contrast, a low-GI food leads to a gentler, more gradual rise in blood glucose.

This places far less stress on the pancreas (in type 2 diabetes) and makes blood sugar levels more predictable and easier to manage with insulin (in type 1 diabetes).

Instead of a volatile “spike and crash” cycle, low-GI foods promote a smoother, more stable energy supply, which is the ultimate goal of glycemic control.

Figure 1: A visual representation of the typical blood glucose response after consuming high-GI versus low-GI foods. The low-GI curve demonstrates a more stable and manageable glycemic profile, which is ideal for diabetes management.

Key Takeaway: The Mechanism

High-GI foods demand a rapid, high-volume insulin response that a diabetic system struggles to provide, leading to glycemic volatility. Low-GI foods require a slower, lower insulin response, promoting blood sugar stability and reducing metabolic stress.

The Scientific Evidence: Improving HbA1c and Glycemic Control

The benefits of a low-GI diet for diabetes are not just theoretical, they are supported by a robust body of scientific evidence.

Numerous clinical trials and meta-analyses have consistently shown that adopting a low-GI eating pattern can lead to clinically significant improvements in glycemic control.

The most important marker for long-term blood sugar management is Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), which reflects average blood glucose levels over the preceding 2-3 months.

A recent comprehensive review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in 2024 confirmed that low-GI and low-GL dietary patterns contribute to minimizing fluctuations in blood glucose.

The review highlighted that most RCTs consistently reported that low-GI/GL diets led to improved HbA1c levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Another meta-analysis of 29 studies involving over 1.600 patients with diabetes found that low-GI diets decreased HbA1c by an average of 0.31%.

While this may seem like a modest number, even small reductions in HbA1c are associated with a significant decrease in the risk of long-term diabetic complications.

For example, the landmark UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) showed that every 1% reduction in HbA1c can reduce the risk of microvascular complications (like eye, nerve and kidney disease) by up to 37%.

“The consistent evidence suggests that adopting low-GI and low-GL diets can improve HbA1c and postprandial glycemic control in individuals with T2DM. This dietary pattern may also contribute to minimizing blood glucose fluctuations and reducing inflammatory responses”. — The role of low glycemic index and load diets in medical nutrition therapy for type 2 diabetes: an update (2024)

Beyond Blood Sugar: Additional Health Benefits for Diabetics

While improved glycemic control is the primary benefit, the advantages of a low-GI diet extend to other critical areas of health for people with diabetes, who are often at higher risk for related conditions.

- Weight Management: Many low-GI foods are high in fiber and protein, which increase feelings of fullness (satiety). A 2023 review of studies found that low-GI/GL interventions led to reductions in body weight, BMI, and waist circumference, even in the absence of explicit calorie restriction. Since excess weight is a major driver of insulin resistance, this makes a low-GI diet a powerful tool for managing type 2 diabetes.

- Cardiovascular Health: Diabetes significantly increases the risk of heart disease. Research indicates that low-GI diets can help mitigate this risk. Some studies have shown improvements in cholesterol profiles, particularly an increase in “good” HDL cholesterol. Furthermore, low-GI diets have been linked to a reduction in systemic inflammation, as measured by markers like C-reactive protein (CRP). Chronic inflammation is a key contributor to atherosclerosis (the hardening of arteries).

- Reducing Complication Risks: Emerging long-term research suggests that the benefits may extend to protecting against diabetic complications. One multi-year study found that a low-GI diet helped preserve kidney function (as measured by eGFR) and slowed the progression of atherosclerosis compared to a control diet. This points to the potential of a low-GI eating pattern to not just manage daily blood sugar, but to actively protect the body from the long-term damage caused by diabetes.

Part 3: Glycemic Index vs. Glycemic Load: A Crucial Distinction

While the glycemic index is a foundational concept, relying on it alone can sometimes be misleading.

To make truly practical and effective food choices, it’s essential to understand its partner concept: the glycemic load (GL).

This section clarifies the difference and explains why GL is often the more valuable metric for real-world diabetes management.

Defining Glycemic Load (GL): Adding Portion Size to the Equation

If the glycemic index (GI) tells you how fast a carbohydrate raises blood sugar, the glycemic load (GL) tells you how much it will raise blood sugar in a typical serving.

It provides a more complete picture by factoring in both the quality (GI) and the quantity (the amount of carbohydrates) of the food you eat.

The calculation is straightforward:

GL = (GI of the food × Grams of Carbohydrates per serving) / 100

Like the GI, the GL is also categorized into low, medium, and high ranges:

- Low GL: 10 or less

- Medium GL: 11 to 19

- High GL: 20 or more

The goal for diabetes management is to keep the GL of individual meals, and the total GL for the day, within a low to moderate range.

The Watermelon Example: Why Context Matters

The classic example that illustrates the importance of GL is watermelon.

Watermelon has a high GI of around 72-80, which might lead someone to believe it’s a “bad” food for diabetes. However, this is where context is key.

Watermelon is mostly water. A standard serving (about 1 cup, or 120g) contains only about 6-7 grams of carbohydrates. Let’s calculate its glycemic load:

GL = (72 × 6g) / 100 = 4.32

With a GL of just 4, a serving of watermelon has a very low impact on blood sugar, despite its high GI.

You would have to eat a very large quantity of watermelon for it to cause a significant glucose spike.

This demonstrates that a small portion of a high-GI food can be perfectly acceptable within a diabetes-friendly diet.

GI vs. GL: Which Is More Important for Diabetics?

Both metrics have their place, but for day-to-day meal planning, the glycemic load is generally considered the more practical and powerful tool.

This table summarizes their key differences and applications.

| Glycemic Index (GI) | Glycemic Load (GL) |

|---|---|

| Measures how fast carbohydrates in a food raise blood sugar. | Measures the total impact of a serving of food on blood sugar. |

| Represents the quality of the carbohydrate. | Represents both the quality and quantity of the carbohydrate. |

| Does not account for portion size, which can be misleading. | Directly incorporates portion size, making it more practical for real-world eating. |

| Useful for comparing the potential impact of two foods with similar carb content (e.g., white bread vs. whole wheat bread). | Better for planning a whole meal or an entire day’s diet. The goal is to keep the total GL of a meal low. |

| Example Question: “Which is likely to spike my sugar faster, a potato or lentils?” | Example Question: “What will be the actual impact on my blood sugar if I eat this one-cup serving of pasta?” |

Putting It Together: Using GI and GL for Smarter Meal Planning

The ultimate strategy for diabetes management is to combine both concepts.

Use the glycemic index as a general guide to choose better-quality carbohydrates (favoring low-GI options).

Then, use the glycemic load to manage your portion sizes and build balanced meals.

A meal’s total GL is the sum of the GLs of all its carbohydrate-containing components.

By pairing a small portion of a medium- or high-GI food with plenty of low-GI foods (like non-starchy vegetables) and sources of protein and fat, you can easily create a delicious and satisfying meal with an overall low glycemic load.

Part 4: The Practical Guide: Implementing a Low-GI Diet

Understanding the theory is one thing, putting it into practice is another.

This section provides actionable steps, tools, and examples to help you seamlessly integrate a low-glycemic approach into your daily life.

This is about making sustainable changes, not adopting a restrictive, short-term diet.

Building Your Low-Glycemic Plate: The Swap, Don’t Stop, Method

A successful low-GI diet is not about deprivation.

It’s about making intelligent substitutions. Instead of eliminating food groups, focus on swapping high-GI items for their lower-GI counterparts.

This approach is more sustainable and less overwhelming.

- Swap white rice (GI ~73) for quinoa (GI ~53), barley (GI ~28), or brown rice (GI ~68, but check portion size).

- Swap a baked potato (GI ~111) for a boiled sweet potato (GI ~63), lentils (GI ~32), or chickpeas (GI ~28).

- Swap instant oatmeal (GI ~79) for steel-cut or rolled oats (GI ~55).

- Swap white bread (GI ~75) for 100% whole-grain bread or authentic sourdough (GI ~54).

- Swap sugary breakfast cereals for a bowl of Greek yogurt with berries and nuts.

The Ultimate Glycemic Index Food Chart

Having a reliable food list is one of the most valuable assets when starting a low-GI diet.

The following chart provides a comprehensive, though not exhaustive, list of common foods and their approximate GI values.

Use it as a guide for grocery shopping and meal planning.

Note that values can vary slightly based on variety, ripeness, and preparation method.

| Food Category | Low GI (55 or less) | Medium GI (56-69) | High GI (70 or more) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | Cherries (22), Grapefruit (25), Pears (38), Apples (39), Plums (40), Strawberries (40), Peaches (42), Oranges (43), Grapes (53), Berries | Kiwi (58), Mango (60), Bananas (62), Pineapple (66), Raisins (66) | Watermelon (76), Dates (103 – but low GL in small amounts) |

| Vegetables | Broccoli, Cauliflower, Spinach, Kale, Lettuce, Onions, Peppers, Tomatoes, Carrots (raw, 16), Green Beans, Asparagus (all very low GI) | Sweet Corn (52 – borderline low), Boiled Sweet Potato (63), Beets (64) | Pumpkin (75), Parsnips (97), Boiled Potato (78), Baked Russet Potato (111) |

| Grains & Cereals | Barley (28), Quinoa (53), Steel-cut/Rolled Oats (55), All-Bran (45), Buckwheat (54), Sourdough Bread (~54), Whole Wheat Pasta (al dente, ~48) | Pita Bread (57), Brown Rice (68), Couscous (65), Rye Bread (65) | White Bread (75), Instant Oats (79), White Rice (73), Rice Cakes (82), Cornflakes (81), Puffed Rice (82) |

| Legumes | Lentils (32), Kidney Beans (24), Chickpeas (28), Black Beans (30), Soybeans (16), Split Peas (32) – All are excellent choices. | N/A – Most legumes are low GI. | N/A |

| Dairy & Alternatives | Whole/Skim Milk (37-41), Plain Yogurt (14), Soy Milk (34), Almond Milk (unsweetened, ~25) | Ice Cream (51-62, fat lowers GI but high in sugar/calories) | Rice Milk (86) |

| Sweeteners | Fructose (in fruit, 15), Agave Nectar (~15, but high in fructose) | Coconut Sugar (54), Maple Syrup (54), Honey (61) | Table Sugar/Sucrose (65 – borderline medium), High Fructose Corn Syrup (~73), Glucose (100) |

Data compiled from Harvard Health, Healthline, and the University of Sydney’s GI Database.

A Sample 3-Day Low-GI Meal Plan for Diabetics

Here is a sample meal plan to illustrate how these principles come together in delicious, satisfying and blood-sugar-friendly meals.

Portions should be adjusted based on individual needs.

Day 1

- Breakfast: 1/2 cup steel-cut oats cooked with water or milk, topped with 1/2 cup mixed berries and a tablespoon of chopped walnuts.

- Lunch: Large mixed greens salad with grilled chicken breast, chickpeas, cucumber, tomatoes, and a vinaigrette dressing made with olive oil and vinegar.

- Dinner: Baked salmon fillet with a side of quinoa and steamed asparagus drizzled with lemon juice.

- Snack: An apple with a tablespoon of almond butter.

Day 2

- Breakfast: Two scrambled eggs with spinach and mushrooms, served with one slice of 100% whole-grain or sourdough toast.

- Lunch: A bowl of lentil soup with a side salad.

- Dinner: Turkey and black bean chili (no sugar added) topped with a dollop of plain Greek yogurt and a sprinkle of avocado.

- Snack: A small pear and a handful of almonds.

Day 3

- Breakfast: Plain Greek yogurt with a sprinkle of cinnamon, 1/4 cup of low-sugar granola (like All-Bran), and sliced peaches.

- Lunch: Leftover turkey and black bean chili.

- Dinner: Chicken and vegetable stir-fry (using broccoli, bell peppers, snow peas) with a light soy-ginger sauce, served over a small portion of barley.

- Snack: Raw carrot and celery sticks with hummus.

Grocery Shopping and Label Reading Tips

Navigating the grocery store can be easier with a few key strategies:

- Shop the perimeter: This is where you’ll find most whole, unprocessed foods like fresh fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and dairy—the foundation of a low-GI diet.

- Choose intact whole grains: Look for grains you can see, like steel-cut oats, barley, quinoa, and farro, rather than finely milled flours.

- Read the ingredients list: The shorter, the better. Be wary of products with sugar, high fructose corn syrup, or refined flours listed in the first few ingredients.

- Look for fiber: When choosing packaged foods like bread or crackers, compare labels and pick the option with more dietary fiber per serving. Fiber helps to lower the GI.

- Beware of “low-fat” claims: Often, when fat is removed from a product, sugar is added to improve the taste, which can dramatically increase the GI. Compare the sugar content on the nutrition label.

Part 5: The Nuances: What Else Affects a Food’s GI?

The glycemic index is not a static number.

Several factors can influence how a food affects your blood sugar, and understanding these nuances allows for even greater control and flexibility in your diet.

This is where you can move from following a chart to truly understanding food.

Ripeness

The ripeness of a fruit or vegetable can significantly alter its GI.

As a fruit ripens, its complex carbohydrates (starches) break down into simpler sugars.

A classic example is the banana: a slightly green, under-ripe banana has a GI of around 30-40 because it’s high in resistant starch.

A ripe, yellow banana with brown spots has a much higher GI of 60 or more, as that starch has converted to fructose and glucose.

Cooking Method & Time

How you prepare a food can change its starch structure and, therefore, its GI.

- Cooking Time: The longer you cook a carbohydrate like pasta or rice, the more its starch gelatinizes and becomes easier to digest, raising the GI. Cooking pasta until it is al dente (firm to the bite) results in a lower GI than cooking it until it is soft.

- Cooking Method: Boiling tends to result in a lower GI compared to baking or roasting. For example, a boiled potato has a significantly lower GI than a baked potato of the same variety. Frying can sometimes lower the GI because the added fat slows stomach emptying, but this is not a recommended health strategy due to the extra calories and unhealthy fats.

The Power of Combination: The “Meal Effect”

You rarely eat a carbohydrate in isolation.

The other components of your meal have a powerful effect on the overall glycemic response.

This is perhaps the most important nuance to master.

- Fat and Protein: Adding a source of healthy fat (like avocado, nuts, or olive oil) or lean protein (like chicken or fish) to a meal slows down the rate at which your stomach empties. This, in turn, slows the absorption of glucose into the bloodstream, effectively lowering the overall GI of the entire meal. This is why a slice of bread eaten with avocado has a much gentler impact on blood sugar than a slice of bread eaten alone.

- Fiber: Soluble fiber, found in foods like oats, beans and apples, forms a gel-like substance in the digestive tract that slows digestion and glucose absorption. This is a primary reason why high-fiber foods almost always have a low GI.

Acidity

Adding an acidic component to your meal can also help lower its glycemic impact.

Acids, such as vinegar (acetic acid) or lemon juice (citric acid), have been shown to slow gastric emptying and may even improve insulin sensitivity.

This is why a vinaigrette dressing on a salad or a squeeze of lemon over a meal can be a simple yet effective strategy to blunt a potential blood sugar rise.

Expert Tip: The “Dress Your Carbs” Rule

A simple rule of thumb is to never eat a “naked” carbohydrate. Always “dress” it with a source of fiber, protein, or healthy fat. Add a handful of nuts to your oatmeal, top your toast with an egg or mix your rice with vegetables and beans. This simple habit can dramatically lower the glycemic load of your meals.

Part 6: A Balanced View: Limitations of the Glycemic Index

To build trust and provide a truly authoritative guide, it’s essential to acknowledge that the glycemic index is not a perfect system.

While it is an incredibly valuable tool, it has limitations.

A balanced perspective is key to using it effectively without falling into common traps.

“Low-GI” Doesn’t Always Mean “Healthy”

One of the biggest pitfalls of focusing solely on the GI is assuming that any low-GI food is a good choice.

This is not always the case. The GI value tells you nothing about a food’s overall nutritional content, such as its calorie density, fat type, sodium or vitamin and mineral content.

For example, potato chips and ice cream can have a medium-to-low GI because their high fat content slows glucose absorption.

However, they are high in calories, unhealthy fats, and/or added sugars, making them poor choices for overall health, especially for weight management and cardiovascular risk.

Conversely, some highly nutritious vegetables like parsnips have a high GI, but they are packed with vitamins and fiber and have a low glycemic load in a typical serving.

Individual Variability

The published GI values are averages from tests on small groups of people. In reality, an individual’s blood sugar response to a specific food can vary.

Factors that influence this include:

- Genetics and Metabolism: Each person’s metabolic rate and insulin sensitivity are unique.

- Gut Microbiome: The composition of your gut bacteria can influence how you digest and absorb carbohydrates.

- Time of Day: Many people, particularly those with insulin resistance, are more insulin sensitive in the morning than in the evening.

- Physical Activity: Your blood sugar response to a meal can be different if you’ve recently exercised.

The best approach is to use GI charts as a starting guide, but also to monitor your own blood sugar to learn how your body responds to different foods.

The Big Picture: GI as One Tool in Your Toolbox

The glycemic index should not be the only principle guiding your diet.

It is one important tool in a comprehensive diabetes management plan.

It should be used in conjunction with other established strategies:

- Carbohydrate Counting: Especially for those on insulin, knowing the total amount of carbs in a meal is essential for correct dosing.

- Portion Control: The glycemic load concept already incorporates this, but it’s a fundamental principle for all aspects of healthy eating.

- Nutrient Density: Prioritize foods that are rich in vitamins, minerals, and fiber, regardless of their GI.

- Overall Dietary Pattern: A Mediterranean-style or DASH diet pattern, which are naturally rich in low-GI foods, have been proven to be highly beneficial for both diabetes and heart health.

Think of the glycemic index as a compass, not a rigid map. It points you in the right direction—toward whole, minimally processed, high-fiber carbohydrates—but you must still use your judgment to navigate the terrain of overall nutrition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Can I still eat high-GI foods if I have diabetes?

A: Yes, in moderation. The key is portion control and pairing them with low-GI foods, protein, and fat to blunt the blood sugar response. The overall glycemic load (GL) of the meal is more important than the GI of a single ingredient.

Q2: Is a low-GI diet the same as a low-carb or keto diet?

A: No. A low-GI diet focuses on the quality of carbohydrates, not eliminating them. Many healthy, high-fiber carbohydrates like beans, lentils, and whole grains are staples of a low-GI diet, whereas they are restricted on low-carb and keto diets.

Q3: What are the best low-glycemic fruits for diabetics?

A: Berries (strawberries, blueberries, raspberries), cherries, apples, pears and citrus fruits (oranges, grapefruit) are excellent low-GI choices. They are also high in fiber and nutrients, making them ideal for diabetes management.

Q4: Does a low-GI diet guarantee weight loss?

A: While many people lose weight on a low-GI diet due to increased satiety from fiber and protein, weight loss still depends on overall calorie balance. It’s a tool to help create a calorie deficit more easily, not a magic bullet.

Q5: How do I find the GI of a food that’s not on a chart?

A: You often can’t find an official value for every food. As a general rule, foods that are high in fiber, protein, or fat, and those that are less processed and more “intact,” tend to have a lower GI.

Q6: Is the glycemic index useful for type 1 diabetes?

A: Yes. While insulin dosing for the carbohydrate amount is paramount, choosing lower-GI foods can help prevent sharp post-meal blood sugar spikes and make glucose levels more predictable and easier to manage with insulin, reducing glycemic variability.

Q7: What is a good low-GI breakfast for a person with diabetes?

A: Options include steel-cut oatmeal with nuts and berries, scrambled eggs with vegetables and a slice of sourdough toast, or a smoothie made with plain Greek yogurt, spinach, and low-GI fruit like berries.

Q8: Does drinking vinegar really lower a meal’s GI?

A: Yes, studies show that the acetic acid in vinegar can slow stomach emptying and improve insulin sensitivity, which helps lower the overall glycemic response of a meal. A tablespoon in a glass of water or as part of a salad dressing can be beneficial.

Conclusion

The glycemic index is far more than a dietary buzzword, it is a vital, evidence-based tool that can empower individuals with diabetes to gain meaningful control over their blood sugar and long-term health.

By understanding that the GI measures the speed of glucose release, you can begin to make smarter carbohydrate choices.

We’ve seen that the glycemic load provides an even more practical, real-world picture by incorporating portion size, turning confusing data into actionable meal plans.

A diet rich in low glycemic foods—vegetables, legumes, intact grains, and certain fruits—is scientifically proven to improve HbA1c, aid in weight management and reduce the risk of devastating diabetic complications.

Your journey to better blood sugar control can start today.

Begin by swapping just one high-GI food in your daily diet for a low-GI alternative—white bread for sourdough, a sugary cereal for oatmeal.

For a personalized plan that aligns with your health goals and lifestyle, discuss incorporating the glycemic index with your doctor or a registered dietitian.

What’s your favorite low-GI food or recipe? Share it in the comments below to help others in the community!

Reference

[1] https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/glycemic-index

[2] Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load | Linus Pauling Institute

https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/food-beverages/glycemic-index-glycemic-load

[3] Carbohydrates and the glycaemic index

https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/carbohydrates-and-the-glycaemic-index

[6] The role of low glycemic index and load diets in medical …

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11519289

[7] The Health Effects of Low Glycemic Index and …

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10746079

[8] The effectiveness of a community-based online low-glycaemic …

https://archpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13690-025-01552-0

[9] A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Low-Glycemic …

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2330083

[10] Glycemic Load vs. Index: Tools for Blood Sugar Control

https://www.verywellhealth.com/glycemic-index-vs-load-5214363

[11] The lowdown on glycemic index and glycemic load