Vitamin B12 is crucial for energy production, but it only boosts energy levels in individuals who are correcting a deficiency.

For those with adequate B12, supplements will not provide an energy surge.

The widespread belief that it’s a universal energy enhancer is a common, yet persistent, misconception.

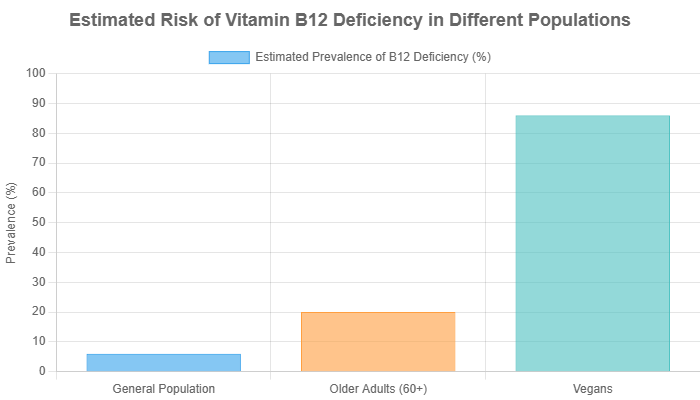

This misunderstanding isn’t trivial. Vitamin B12 deficiency can affect up to 15% of the general population, and its prevalence climbs significantly higher among older adults and those on plant-based diets, making fatigue a significant and often misattributed symptom.

This gap between myth and reality leads many to chase an energy boost they’ll never find, while others miss the true cause of their exhaustion.

This article will dissect the intricate science behind vitamin B12’s role in your body’s energy systems.

We will debunk the pervasive myths surrounding B12 “energy shots” and provide a clear, evidence-based guide to understanding if this essential nutrient is the real answer to your fatigue.

Continue reading to determine if a lack of vitamin B12 is what’s truly holding your energy levels back.

In This Article

Part 1: What is Vitamin B12 and Why is it Essential?

Before we can understand the connection between vitamin B12 and energy, it’s crucial to establish a foundational understanding of what this vitamin is and the indispensable roles it plays throughout the human body.

Its importance extends far beyond the realm of metabolism, touching nearly every aspect of our physiological and neurological health.

What is Vitamin B12?

Vitamin B12, known scientifically as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin that contains the mineral cobalt, giving it a distinctive red color.

Unlike many other vitamins, our bodies cannot produce vitamin B12 on their own.

Therefore, we must obtain it regularly through our diet or supplementation.

It is naturally found almost exclusively in animal-derived products, a fact that has significant implications for dietary planning, especially for vegetarians and vegans.

Once consumed, vitamin B12 undergoes a complex absorption process. It must first be separated from food proteins by stomach acid and then bind to a protein called intrinsic factor, which is produced in the stomach.

This B12-intrinsic factor complex then travels to the final section of the small intestine (the terminal ileum), where it is absorbed into the bloodstream.

Any disruption in this intricate pathway can lead to a deficiency, even with adequate dietary intake.

Core Bodily Functions: The Pillars of Health

The influence of vitamin B12 is systemic. It acts as a critical cofactor—a “helper molecule”—for two major enzymes that drive fundamental biochemical reactions.

These reactions are central to three pillars of health:

- Nerve Function and Myelin Sheath Maintenance: Vitamin B12 is indispensable for the health of our nervous system. It plays a vital role in the synthesis and maintenance of the myelin sheath, a fatty substance that insulates nerve fibers. A healthy myelin sheath allows for rapid and efficient transmission of nerve signals. A deficiency can lead to demyelination, causing irreversible neurological damage, manifesting as numbness, tingling, balance problems and cognitive decline.

- DNA Synthesis: Every time a cell in your body divides, it must create an exact copy of its DNA. Vitamin B12 is a key player in this process, particularly in the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines, the building blocks of DNA. Without sufficient B12, cell division is impaired, affecting rapidly dividing cells most severely, such as those in the bone marrow.

- Red Blood Cell Formation (Erythropoiesis): Directly linked to its role in DNA synthesis, vitamin B12 is essential for the proper maturation of red blood cells in the bone marrow. A deficiency disrupts this process, leading to the production of large, immature and dysfunctional red blood cells, a condition known as megaloblastic anemia. We will explore this in greater detail in Part 2.

How Much Vitamin B12 Do You Need?

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for vitamin B12 varies by age, life stage and specific health conditions.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Dietary Supplements, the general recommendations are as follows:

- Adults (19+ years): 2.4 micrograms (mcg) per day.

- Pregnant Women: 2.6 mcg per day.

- Lactating Women: 2.8 mcg per day.

It’s important to note that these RDAs are set to prevent deficiency in the vast majority of healthy individuals.

However, certain populations, such as older adults, may have higher needs or reduced absorption capabilities.

The NIH suggests that adults over 50 should get most of their B12 from fortified foods or supplements, as they may be less able to absorb the food-bound form of the vitamin due to decreased stomach acid production.

Part 2: How Does Vitamin B12 Actually Affect Energy Levels?

This is the central question that fuels the multi-million dollar market for B12 supplements and injections.

The perception of vitamin B12 as a direct “energy booster” is pervasive, but the scientific reality is more nuanced.

It doesn’t provide energy in the way that carbohydrates or fats do.

Instead, it is an essential facilitator of the body’s own energy-producing machinery.

Its effect on energy is felt most profoundly when a deficiency is corrected, restoring broken metabolic and physiological processes.

The Cellular Engine: B12’s Role in Metabolism

The energy our bodies use for everything from breathing to thinking is a molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

ATP is generated within our cells mitochondria through a series of complex biochemical reactions, most notably the Krebs cycle (also known as the citric acid cycle).

B vitamins, including B12, do not contain energy themselves, they act as essential cofactors that allow these reactions to occur.

Think of it this way: if your body’s metabolic engine is what burns fuel (food) to create power (ATP), then vitamin B12 is the spark plug.

The engine has plenty of gasoline (calories), but without the spark plug, it cannot ignite the fuel to generate power.

Specifically, vitamin B12 is a required cofactor for the enzyme L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase.

This enzyme performs a critical step in converting certain fats and proteins into succinyl-CoA, a compound that directly enters the Krebs cycle to produce ATP.

When B12 is deficient, this pathway is blocked. The precursor, methylmalonyl-CoA, builds up (which is why methylmalonic acid, or MMA, is a key marker for deficiency), and the cell’s ability to generate energy from these sources is impaired.

Correcting the deficiency “unclogs” this pathway, allowing the cellular engine to run efficiently again.

Analogy: Vitamin B12 is the spark plug for your cellular engine, not the gasoline. It enables the conversion of fuel into energy but doesn’t provide the fuel itself.

The Oxygen Delivery System: B12 and Red Blood Cells

A second, equally important mechanism through which vitamin B12 impacts energy is its role in the production of healthy red blood cells.

As discussed in Part 1, B12 is vital for DNA synthesis, which is necessary for cell division.

The bone marrow, where red blood cells are born, is one of the most active sites of cell division in the body.

In a state of vitamin B12 deficiency, this process goes awry.

The bone marrow produces red blood cells that are abnormally large and oval-shaped, instead of small and round.

This condition is known as megaloblastic anemia. These malformed cells have two major problems:

- They are fragile: They have a shorter lifespan and are destroyed more easily, leading to a lower overall red blood cell count (anemia).

- They are inefficient: Their irregular shape impairs their ability to carry oxygen effectively from the lungs to the rest of the body.

The connection to energy is direct and profound.

Oxygen is the final, critical component required by our mitochondria to produce ATP efficiently.

When tissues, especially muscles and the brain, are deprived of adequate oxygen (a state called hypoxia), they cannot generate enough energy to function optimally.

This results in the classic and debilitating symptoms of anemia: profound fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath and a feeling of being completely drained.

The Critical Distinction: Correcting a Deficiency vs. Creating a Boost

Synthesizing these two mechanisms reveals the core truth about vitamin B12 and energy.

The “energy boost” people experience from B12 supplementation is almost exclusively the result of reversing a state of deficiency.

- If you are deficient: Your cellular engines are sputtering, and your oxygen delivery system is failing. Providing B12 is like installing new spark plugs and fixing the oxygen supply chain. The result is a dramatic restoration of normal energy levels, which feels like a powerful boost.

- If you are sufficient: Your cellular engines are already running smoothly, and your red blood cells are efficiently delivering oxygen. Your metabolic pathways are not “clogged” and your oxygen supply is not compromised. Adding more B12 is like adding extra spark plugs to an already functioning engine—it provides no additional benefit. The body will simply excrete the excess.

This conclusion is strongly supported by robust scientific evidence. The Mayo Clinic states clearly, “There’s no proof that taking vitamin B-12 supplements or injections boosts energy or improves athletic performance” in people who are not deficient.

Furthermore, a comprehensive 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis published in the journal Nutrients investigated the effects of B12 supplementation and found it was likely ineffective for improving fatigue in patients without advanced neurological disorders or overt deficiency.

The myth persists because the relief felt by those who are truly deficient is so significant that it creates a powerful narrative.

However, for the general population with adequate B12 levels, the promise of an energy surge from a B12 shot or pill remains just that—a promise, not a physiological reality.

Part 3: Could You Have a Vitamin B12 Deficiency?

Given that the energy-restoring benefits of vitamin B12 are tied directly to deficiency, the most important question becomes: are you deficient?

Recognizing the symptoms and identifying if you fall into a high-risk category are the first critical steps toward getting an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

This section is designed to empower you with the knowledge to have an informed conversation with your healthcare provider.

What are the Symptoms of B12 Deficiency?

Vitamin B12 deficiency can be insidious, with symptoms developing gradually over months or even years.

They can be vague and are often mistakenly attributed to stress or aging.

The symptoms can be broadly categorized into hematological (related to blood) and neurological (related to the nervous system).

It’s crucial to know that neurological symptoms can occur even without the presence of anemia.

Key Symptoms of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

If you experience a combination of these symptoms, especially if you are in a high-risk group, it is essential to consult a doctor.

- Profound Fatigue and Lack of Energy: A persistent, deep-seated exhaustion that isn’t relieved by rest. This is the most common and often the first symptom.

- Weakness: Generalized muscle weakness.

- Pale or Jaundiced Skin: A pale complexion due to anemia, or a yellowish tint to the skin and eyes (jaundice) from the breakdown of fragile red blood cells.

- Shortness of Breath and Dizziness: Caused by the body’s reduced oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Numbness or Tingling (Pins and Needles): Typically in the hands, legs or feet. This is a classic sign of nerve involvement (peripheral neuropathy).

- Difficulty with Balance and Walking: Unsteadiness or coordination problems (ataxia) due to damage to the spinal cord.

- Cognitive Disturbances (“Brain Fog”): Difficulty concentrating, memory loss, confusion and in severe cases, dementia.

- Sore, Red, and Swollen Tongue (Glossitis): The tongue may appear smooth and “beefy”.

- Mouth Ulcers or Canker Sores.

- Vision Disturbances: Blurred or disturbed vision due to damage to the optic nerve.

- Mood Changes: Irritability, depression or changes in feelings and behavior.

Who is Most at Risk for B12 Deficiency?

While anyone can become deficient, certain groups have a significantly higher risk due to dietary choices, age-related physiological changes or underlying medical conditions.

As documented by sources like the NCBI StatPearls, these groups require heightened awareness and often regular screening.

Older Adults (Age 50+)

This is one of the highest-risk groups. Up to 20% of older adults may have a B12 deficiency.

The primary reason is a condition called atrophic gastritis, which involves the thinning of the stomach lining and reduced production of stomach acid.

This acid is necessary to release B12 from the proteins in food. Without it, food-bound B12 cannot be absorbed effectively, even if intake is sufficient.

Vegans and Vegetarians

Since vitamin B12 is found almost exclusively in animal products (meat, fish, poultry, eggs, dairy), individuals following strict vegetarian or vegan diets are at very high risk of deficiency if they do not supplement or consume fortified foods.

Symptoms can take years to develop because the liver can store a significant amount of B12, but deficiency is almost inevitable without proactive intake.

Individuals with Gastrointestinal (GI) Disorders

Any condition that affects the stomach or small intestine can impair B12 absorption. This includes:

- Crohn’s Disease: Inflammation in the terminal ileum, the primary site of B12 absorption, can prevent the B12-intrinsic factor complex from being absorbed.

- Celiac Disease: Damage to the small intestine lining can lead to general malabsorption of many nutrients, including B12.

- Pernicious Anemia: This is an autoimmune disorder where the body’s immune system attacks the stomach cells that produce intrinsic factor. Without intrinsic factor, B12 cannot be absorbed, leading to severe deficiency.

Individuals Who Have Had GI Surgery

Surgical procedures that remove or bypass parts of the stomach or small intestine can permanently reduce B12 absorption.

This is particularly common after bariatric surgery (like gastric bypass) or surgery to remove the terminal ileum.

People on Certain Long-Term Medications

Two common classes of medication are known to interfere with B12 absorption:

- Metformin: A widely prescribed drug for type 2 diabetes, long-term use of metformin has been shown to reduce B12 absorption and lower serum levels.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 Blockers: These medications (e.g., omeprazole, lansoprazole, cimetidine) are used to treat acid reflux and ulcers. By suppressing stomach acid production, they can impair the release of B12 from food over time.

How is B12 Deficiency Properly Diagnosed?

If your symptoms and risk factors suggest a potential deficiency, self-diagnosing and supplementing is not the answer.

A proper medical diagnosis is essential to confirm the deficiency, identify its underlying cause and determine the correct treatment plan.

The diagnostic process typically involves:

- Medical History and Physical Exam: Your doctor will ask about your diet, symptoms, medications and medical history.

- Initial Blood Test (Serum B12): A standard blood test measures the total amount of B12 circulating in your blood. While a low level (typically <200 pg/mL) is a strong indicator of deficiency, this test has limitations. A “normal” or “low-normal” result (200-400 pg/mL) can sometimes be misleading and may not reflect what’s happening at the cellular level.

- Confirmatory Functional Markers: Because of the limitations of the serum B12 test, doctors may order tests for functional markers that provide a more accurate picture of B12 status. These are the gold standard for diagnosing a true, metabolic deficiency:

- Methylmalonic Acid (MMA): As explained in Part 2, MMA accumulates when the B12-dependent enzyme is not working. An elevated MMA level is a highly sensitive and specific indicator of B12 deficiency.

- Homocysteine: This amino acid also builds up when B12 is lacking. While less specific than MMA (it can also be elevated in folate deficiency), a high homocysteine level alongside a borderline B12 level strengthens the case for deficiency.

An accurate diagnosis using these tools is critical. It distinguishes a true B12 deficiency from other causes of fatigue and ensures you receive the treatment that will actually solve the problem.

Part 4: B12 Supplements & Shots: Hype vs. Reality

The wellness industry has transformed vitamin B12 from a medical treatment for deficiency into a mainstream “lifestyle” product.

B12 “energy bars”, IV drips, and walk-in clinics offering “energy shots” are now commonplace.

This section cuts through the marketing hype to provide an evidence-based look at the different forms of B12 supplementation, their effectiveness and who truly benefits from them.

Why are B12 Shots Marketed as an “Energy Booster”?

The reputation of B12 shots as a miracle energy cure has its roots in legitimate medical history.

For decades, intramuscular injections were the primary treatment for pernicious anemia, a once-fatal condition.

Patients suffering from severe, debilitating fatigue would receive a B12 injection and, as their anemia and neurological symptoms resolved, experience a dramatic and life-changing return of energy.

This powerful therapeutic effect was observed and subsequently co-opted by marketing.

The logic became simplified and misapplied: if B12 cures fatigue in sick people, it must give energy to healthy people. This narrative was further amplified by:

- Celebrity Endorsements: High-profile individuals touting B12 shots for energy and wellness created a powerful trend.

- The Placebo Effect: The act of receiving an injection from a professional in a clinical setting can create a strong psychological expectation of benefit. Many people report feeling more energetic simply because they believe they should, a well-documented phenomenon.

- Misattribution: A person who is unknowingly borderline deficient might receive a shot, feel better as their deficiency is corrected, and mistakenly attribute the feeling to a “super-boosting” effect rather than a return to their normal baseline.

While B12 injections remain a critical and effective medical treatment for severe deficiency and malabsorption, their use as a universal energy enhancer for the general public is not supported by science.

Oral vs. Injections vs. Sublingual: Which is Best?

Choosing the right form of B12 depends entirely on the reason for supplementation.

The primary consideration is whether your digestive system can absorb it properly.

Here is a comparison to help you understand the options:

| Form | How it Works | Best For | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Pills | Absorbed in the small intestine. High doses (1000-2000 mcg) can overcome a lack of intrinsic factor through a secondary, less efficient pathway called passive diffusion (about 1% absorption). | Dietary insufficiency (vegans, vegetarians), mild deficiency in those with normal absorption and as an alternative to injections for many with malabsorption. | Cost-effective, convenient, painless, proven effective at high doses. | Ineffective at low doses for malabsorption, requires patient compliance. |

| Injections (Intramuscular) | Bypasses the entire digestive system, delivering B12 directly into the muscle for 100% bioavailability into the bloodstream. | Severe deficiency, pernicious anemia, significant malabsorption (Crohn’s, post-GI surgery), neurological symptoms. | Guaranteed absorption, rapid increase in B12 levels, medically supervised. | Requires a prescription, must be administered by a professional (or self-injected), can be painful, more expensive. |

| Sublingual / Nasal Sprays | Claim to be absorbed directly into the bloodstream through the mucous membranes under the tongue or in the nose, bypassing the stomach. | People who have difficulty swallowing pills, marketed as a superior alternative to oral pills. | Convenient, bypasses stomach acid. | Evidence for superior absorption over high-dose oral pills is weak. Research suggests they are largely comparable in effectiveness to standard oral supplements. |

A key takeaway from modern research is that high-dose oral B12 (1.000-2.000 mcg daily) has been shown to be as effective as intramuscular injections for correcting deficiency in many cases, even in patients with pernicious anemia.

This has challenged the long-held belief that injections are the only option for malabsorption.

Cyanocobalamin vs. Methylcobalamin: Does it Matter?

The supplement aisle presents another choice: different chemical forms of B12. The two most common are:

- Cyanocobalamin: A synthetic, highly stable, and cost-effective form of B12. It is the most studied form and is used in most fortified foods and prescriptions. The body must convert it into an active form (like methylcobalamin) by removing its cyanide molecule (the amount is physiologically insignificant and harmless).

- Methylcobalamin: A naturally occurring, active form of B12. It is marketed as being more “bioavailable” or “superior” because the body does not need to convert it.

While the marketing for methylcobalamin is compelling, the scientific consensus is that both forms are effective at raising B12 levels and correcting deficiency.

Cyanocobalamin’s stability and extensive research history make it a reliable and often more affordable choice.

For most people, the choice between the two is unlikely to make a significant clinical difference.

Some practitioners may prefer methylcobalamin for specific neurological conditions, but this is an area of ongoing research.

The Future of B12: Innovations in Absorption

The challenge of oral B12 absorption has spurred innovation in supplement delivery systems.

The goal is to protect the vitamin from the harsh environment of the stomach and enhance its uptake in the intestine, especially for those with compromised digestive function.

One such emerging technology is Sucrosomial® delivery.

This involves encapsulating the B12 molecule in a lipid-based vesicle.

A 2024 study published in Frontiers in Nutrition compared this technology to conventional oral B12 supplements.

The results showed that Sucrosomial® B12 was significantly more effective at rapidly increasing and maintaining higher serum B12 levels.

This technology aims to bypass the traditional intrinsic factor pathway, potentially offering a highly effective oral alternative for individuals with severe malabsorption issues.

While still new, such innovations demonstrate a move towards more targeted and efficient nutritional therapies.

Part 5: Your Evidence-Based Action Plan

Navigating the information about vitamin B12 and fatigue can be overwhelming.

This section distills the key insights from this article into a simple, step-by-step action plan to help you address your fatigue logically and effectively.

- Step 1: Assess Your Symptoms and Risk Profile. Before anything else, conduct a personal review. Refer back to the comprehensive list of symptoms in Part 3. Are you experiencing more than just tiredness? Do you have any neurological signs like tingling, numbness, or brain fog? Now, consider your risk profile. Are you over 50? Do you follow a plant-based diet? Do you have a GI condition like Crohn’s or take metformin? A “yes” to any of these questions significantly increases the possibility that B12 deficiency could be a factor in your fatigue.

- Step 2: Get Tested, Don’t Guess. This is the most critical step. Resist the urge to self-diagnose and start taking high-dose supplements based on a hunch. Schedule an appointment with your healthcare provider and share your symptom and risk assessment. Insist on a thorough investigation. A simple serum B12 test is a good start, but if the results are borderline or inconclusive, advocate for more definitive testing, such as for methylmalonic acid (MMA) and homocysteine, to get a true picture of your metabolic status.

- Step 3: Focus on a B12-Rich Diet (If Appropriate). While waiting for test results or as a general preventative measure, you can optimize your dietary intake. If you eat animal products, prioritize foods that are exceptionally high in vitamin B12.

- Top Tier Sources: Clams, beef liver, and certain types of fish like trout, salmon, and tuna are packed with B12.Good Sources: Beef, eggs, milk, and dairy products like yogurt and cheese are also excellent contributors to your daily intake.Fortified Foods: Look for nutritional yeast (a vegan favorite with a cheesy flavor), fortified breakfast cereals, and fortified plant-based milks (soy, almond, oat). Check labels to ensure they contain a meaningful amount of vitamin B12.

- Step 4: Supplement Smartly, Based on Medical Advice. If testing confirms a deficiency, your doctor will recommend a treatment plan. This is not a one-size-fits-all scenario. The right approach depends on the cause and severity of your deficiency.

- For Dietary Insufficiency: A standard oral supplement (either cyanocobalamin or methylcobalamin) is usually sufficient.For Confirmed Malabsorption (e.g., pernicious anemia, post-GI surgery): Your doctor may start you on B12 injections to rapidly replenish your stores. They may then transition you to high-dose oral supplements (1.000-2.000 mcg daily) for long-term maintenance, as this has been proven effective for many.

Key Principle: The goal is not to chase a temporary “boost” but to identify and correct the root cause of your fatigue. A methodical, evidence-based approach is always superior to guesswork and marketing hype.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How quickly will I feel more energy after taking B12?

If you are truly deficient, you may start to notice improvements in energy and well-being within a few days to a week of starting treatment, especially with injections. However, for neurological symptoms to improve, it can take several months, and some nerve damage may be permanent if left untreated for too long.

2. Can you take too much vitamin B12?

Vitamin B12 has a very low potential for toxicity. There is no established Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) because no adverse effects have been associated with high intakes in healthy people. Your body absorbs what it needs and excretes the excess in urine.

3. Do B12 supplements help with weight loss?

No. There is no scientific evidence to support the claim that vitamin B12 supplements or injections cause weight loss. This myth likely stems from the idea that more “energy” leads to more activity, but B12 does not directly impact fat metabolism or appetite in a way that promotes weight loss.

4. Will B12 give me energy if I’m not anemic?

Unlikely. If your fatigue is not caused by a B12 deficiency (with or without anemia), then taking extra B12 will not provide an energy boost. Your fatigue is likely due to other factors such as lack of sleep, stress, other nutrient deficiencies (like iron), or an underlying medical condition.

5. Is a B12 shot better than a pill for energy?

A shot is only “better” if you have a condition that prevents you from absorbing B12 from your gut (malabsorption). For people with normal digestion, high-dose oral pills (1000-2000 mcg) have been shown to be just as effective as injections at correcting a deficiency.

6. What’s the best time of day to take vitamin B12?

It’s generally recommended to take B vitamins in the morning. Since they play a role in energy metabolism, taking them late at night could theoretically interfere with sleep for some sensitive individuals, although this is not a universal experience.

7. Does vitamin B12 help with “brain fog”?

Yes, if the brain fog is a symptom of a B12 deficiency. Cognitive issues like confusion, memory problems, and difficulty concentrating are classic neurological symptoms of low B12. Correcting the deficiency can significantly improve these symptoms.

8. Are all B12 supplements vegan?

No. While the B12 itself is produced by microorganisms and is vegan, supplements can be formulated in gelatin capsules (an animal product). Vegans should look for supplements that are explicitly labeled as “vegan” or come in vegetable-based capsules.

9. Can I get enough B12 on a vegetarian diet?

Yes. Lacto-ovo vegetarians can get sufficient B12 from dairy products and eggs. However, intake can still be low, so monitoring is a good idea. For vegans, who consume no animal products, supplementation or consistent intake of fortified foods is essential.

10. What are the signs of high B12 levels?

While excess B12 is generally considered safe, some observational studies have noted associations between very high B12 levels (often from supplementation) and certain health risks, though causality is not established. Some people may experience mild side effects like acne, anxiety, or headaches from very high doses, but this is uncommon.

Conclusion

The relationship between vitamin B12 and energy is one of the most misunderstood topics in modern wellness.

We’ve journeyed through the science and dismantled the myths to arrive at a clear, evidence-based conclusion.

Vitamin B12 is not a magic bullet for fatigue. It is a fundamental, non-negotiable component of our body’s machinery, essential for converting food into cellular energy and for producing the red blood cells that deliver life-giving oxygen to our tissues.

Its power to “boost” energy is, in reality, the power to restore normal function when that machinery is broken due to a deficiency.

For the millions who are deficient—the elderly, those on plant-based diets, or individuals with digestive disorders—identifying and correcting this shortfall can be life-changing, lifting a heavy veil of fatigue and neurological distress.

For those with already sufficient levels, however, the promise of more energy from a B12 supplement is a physiological fallacy. The body can only use what it needs, the rest is simply discarded.

If you are struggling with persistent fatigue, the most effective and responsible step you can take is to resist the allure of a quick fix. Instead, engage with your healthcare provider.

A simple blood test can definitively reveal if a vitamin B12 deficiency is the true culprit, setting you on a path to a real, lasting solution rather than a temporary and often illusory, fix.

Have you used vitamin B12 for energy? Share your experience or questions in the comments below!

References

- National Institutes of Health. (2025). Vitamin B12: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB12-HealthProfessional/

- Ankar, A., & Kumar, A. (2024). Vitamin B12 Deficiency. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441923/

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2025). Vitamin B-12. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements-vitamin-b12/art-20363663

- O’Leary, F., & Samman, S. (2010). Vitamin B12 in Health and Disease. Nutrients, 2(3), 299–316. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3257642/

- van de Lagemaat, E. E., de Groot, L. C., & van den Heuvel, E. G. (2021). Effects of Vitamin B12 Supplementation on Cognitive Function, Depressive Symptoms, and Fatigue: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Nutrients, 13(3), 923. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33809274/

- Healthline. (n.d.). 9 Health Benefits of Vitamin B12, Based on Science. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/vitamin-b12-benefits

- Khan, M. A., et al. (2024). Comparative bioavailability study of supplemental oral Sucrosomial® vitamin B12 versus conventional vitamin B12 formulations in a healthy Pakistani population. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1493593/full