Vertigo is a specific symptom, not a disease, characterized by a false sensation that you or your surroundings are spinning.

While often used interchangeably with dizziness, vertigo is distinct.

The most common causes stem from problems within the inner ear, such as Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), but in some cases, it can signal more serious issues in the brain.

This condition is far from rare. Affecting a significant portion of the population, the lifetime prevalence of vertigo and dizziness is estimated to be between 20% and 30%, according to research published in Nature’s Scientific Reports.

This means millions of people will experience this disorienting sensation at some point in their lives, often without understanding its origin.

This guide is designed to demystify vertigo. We will explore the crucial difference between vertigo and general dizziness, break down the specific causes from the most common to the rare, explain how doctors diagnose the issue, and detail a full spectrum of effective treatment options.

Continue reading to pinpoint the potential cause of your symptoms and discover the most effective paths to relief.

In This Article

What is Vertigo, Really? It’s More Than Just Dizziness

Understanding vertigo begins with a critical distinction: it is not the same as feeling dizzy. While all vertigo is a form of dizziness, not all dizziness is vertigo.

This separation is the first step a healthcare professional takes in diagnosing the underlying issue.

The core concept of vertigo is a false sensation of movement. It’s the perception that either you are spinning or the world around you is spinning, much like the feeling after getting off a merry-go-round.

This sensation is generated by a dysfunction in your body’s balance system.

Key Differentiations: Vertigo vs. Dizziness vs. Disequilibrium

- Vertigo: A distinct rotational or spinning sensation. The defining characteristic is the illusion of movement.

- Dizziness: A broad, non-specific term that can encompass a variety of feelings, including lightheadedness (feeling like you might faint), wooziness, or feeling “spaced out”.

- Disequilibrium: This is a feeling of unsteadiness or being off-balance, primarily experienced while standing or walking. It feels less like the world is spinning and more like you are about to fall.

To grasp why this happens, we need to look at the vestibular system.

Think of this system as your body’s internal carpenter’s level. It’s a complex network of parts in your inner ear and pathways in your brain that provides your sense of balance and spatial orientation.

The inner ear contains three semicircular canals filled with fluid and tiny hair-like sensors. As your head moves, the fluid moves, bending the sensors.

This information, along with signals from your eyes and sensory nerves in your body, is sent to the brain.

The brain integrates these signals to create a stable picture of your position in space.

Vertigo occurs when there’s a mismatch or conflict in the signals the brain receives.

For example, if your inner ear tells your brain you’re spinning, but your eyes say you’re sitting still, the resulting confusion manifests as the disorienting sensation of vertigo.

What Are the Telltale Symptoms of a Vertigo Episode?

Recognizing the specific symptoms of vertigo is crucial for communicating effectively with your doctor and getting an accurate diagnosis.

While the spinning sensation is the hallmark, it is often accompanied by a cluster of other physical and sensory disturbances.

Primary Symptoms

These symptoms are directly related to the false sense of motion and imbalance:

- A spinning or whirling sensation: This is the defining symptom of vertigo. It can be mild and brief or severe and prolonged.

- Tilting or swaying: A feeling that the floor is tilting or that you are swaying even when standing still.

- Feeling pulled in one direction: A sensation of being forcefully drawn or pushed to one side.

- Unsteadiness and loss of balance: This can make walking difficult or impossible during an episode, leading to a high risk of falls.

Associated Symptoms

These symptoms are the body’s reaction to the confusing signals from the vestibular system:

- Nausea and/or vomiting: The brain’s confusion can trigger the same response as motion sickness.

- Abnormal, jerking eye movements (nystagmus): The eyes may drift and then jerk back in a rhythmic pattern. A doctor can often observe this during an episode and use it to help diagnose the cause.

- Headache or migraine: Vertigo can be a symptom of a vestibular migraine, or the stress of an episode can trigger a tension headache.

- Sweating: A common autonomic response to the distress of a vertigo attack.

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus) or hearing loss: These symptoms point toward causes that affect both the balance and hearing portions of the inner ear, such as Meniere’s disease or labyrinthitis.

From a patient’s perspective, the experience can be deeply unsettling. Many describe the feeling as intensely disorienting and frightening, suddenly making simple tasks like standing up or walking across a room feel like navigating a ship in a storm. This loss of control over one’s own body can lead to significant anxiety and a fear of future attacks.

Peripheral vs. Central: Why Does the Type of Vertigo Matter?

Once vertigo is identified, the next critical step is to determine its origin.

All cases of vertigo fall into one of two categories: peripheral or central.

This classification is not just academic, it’s fundamental to diagnosis and treatment because it points to vastly different underlying causes, ranging from benign and easily treatable to potentially life-threatening.

Peripheral Vertigo

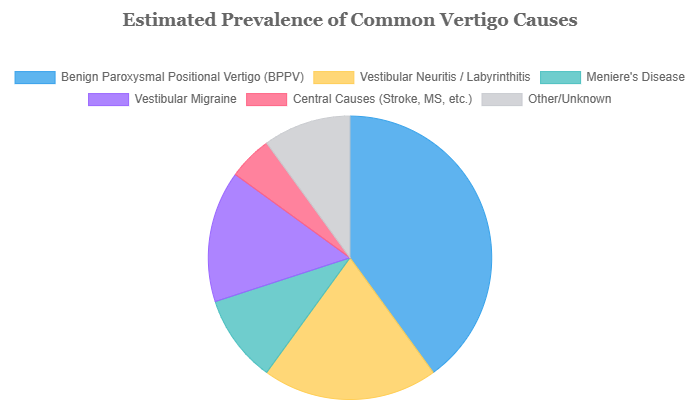

This is by far the most common type, accounting for over 80% of all vertigo cases.

Peripheral vertigo originates from a problem in the inner ear or the vestibular nerve, the nerve that connects the inner ear to the brain. It’s a problem with the “hardware” of the balance system.

The episodes of peripheral vertigo are often more intense and dramatic—think severe, room-spinning sensations.

However, the good news is that the underlying causes are typically not life-threatening and are often highly treatable.

Common causes include BPPV, Meniere’s disease, and vestibular neuritis.

Central Vertigo

This type is less common but generally more serious.

Central vertigo originates from a problem within the brain itself, specifically in the cerebellum or the brainstem.

These are the areas that process balance information. It’s a problem with the “software” or “central processor.”

Symptoms of central vertigo can be more subtle.

The spinning sensation might be less intense, or it may present more as a persistent sense of disequilibrium and unsteadiness.

The most important distinguishing feature is that central vertigo is often accompanied by other neurological signs.

These “red flag” symptoms are a clear signal that something more serious is happening.

The following table provides a clear comparison, which is essential for understanding the differences and recognizing potential warning signs.

| Feature | Peripheral Vertigo | Central Vertigo |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inner Ear / Vestibular Nerve | Brain (Cerebellum/Brainstem) |

| Symptom Intensity | Often intense, severe spinning. Episodes can be debilitating. | Can be less intense, more a constant sense of imbalance or unsteadiness. |

| Episode Pattern | Intermittent, comes in distinct episodes that start and stop. | Often more constant and persistent, may not resolve completely between “attacks.” |

| Associated Symptoms | Nausea, vomiting, hearing loss, and tinnitus are common. Neurological symptoms are absent. | Neurological “red flags” are key: weakness, slurred speech, double vision, trouble swallowing, or severe coordination problems. |

| Common Causes | BPPV, Meniere’s Disease, Labyrinthitis, Vestibular Neuritis. | Stroke, Tumor, Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Vestibular Migraine, Traumatic Brain Injury. |

What’s Causing Your Vertigo? A Deep Dive into the Possibilities

With the framework of peripheral and central vertigo in mind, we can now explore the specific conditions that cause these symptoms.

The following are the most common culprits, starting with the number one cause of vertigo.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): The Most Common Culprit

What it is: BPPV is the single most frequent cause of peripheral vertigo. It’s a mechanical problem within the inner ear. Your inner ear contains tiny calcium carbonate crystals called otoconia.

In BPPV, these crystals become dislodged from their usual location (the utricle) and migrate into one of the fluid-filled semicircular canals, where they don’t belong. A good analogy is thinking of them as “glitter in a snow globe that hasn’t settled.”

Key Symptoms: When you move your head in certain ways (like rolling over in bed, looking up at a high shelf, or bending down to tie your shoes), these loose crystals move within the canal, sending a powerful, false signal to your brain that you are spinning.

This results in short, intense episodes of vertigo that typically last for less than 60 seconds. The vertigo is “paroxysmal” (sudden and brief) and “positional” (triggered by position changes).

Risk Factors: BPPV is more common in people over the age of 50. According to Healthline, it affects women more frequently than men.

Other risk factors include a prior head injury, inner ear disorders, and a potential link to vitamin D deficiency, as suggested by recent studies.

LSI Keyword Integration: The diagnosis of BPPV is often confirmed with a specific test, and thankfully, it is highly treatable with a simple in-office procedure called the Epley maneuver.

Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis: The Role of Infection

What it is: These two conditions are closely related and are caused by inflammation, usually from a viral infection (like the common cold or flu) that attacks the inner ear or its nerve connection to the brain.

- Vestibular Neuritis: This is inflammation of the vestibular nerve. Since this nerve is responsible for balance, the primary symptom is vertigo. Hearing is not affected.

- Labyrinthitis: This is inflammation of the labyrinth, which includes both the vestibular nerve (balance) and the cochlear nerve (hearing).

Key Symptoms: Both conditions cause the sudden onset of severe, constant vertigo that can last for several days.

The feeling is persistent, not positional like BPPV. It can be so intense that it causes severe nausea, vomiting, and the inability to stand or walk.

In the case of labyrinthitis, these symptoms are also accompanied by tinnitus (ringing in the ear) and/or hearing loss on the affected side.

User Experience: Patients often report that the symptoms began a week or two after recovering from a viral illness.

The acute phase is debilitating, but the vertigo gradually subsides over days to weeks as the inflammation resolves and the brain begins to compensate.

Meniere’s Disease: The Pressure Buildup

What it is: Meniere’s disease is a chronic disorder of the inner ear. Its exact cause is unknown, but it’s associated with an abnormal buildup of fluid, called endolymph, in the inner ear.

This buildup increases the pressure within the labyrinth, disrupting both balance and hearing signals.

Key Symptoms (The Classic Triad): Meniere’s disease is characterized by a distinct combination of symptoms that come in spontaneous, recurring episodes:

- Episodic Vertigo: Sudden, severe vertigo attacks that can last from 20 minutes to several hours, but not typically days.

- Fluctuating Hearing Loss: Hearing loss, particularly in the low frequencies, that comes and goes with the attacks.

- Tinnitus and Aural Fullness: A roaring or ringing sound in the ear, combined with a sensation of pressure or fullness, as if the ear is clogged.

Progression: Over time, the attacks can become more frequent, and the hearing loss may become permanent.

The unpredictable nature of the attacks can be particularly distressing for those living with the condition.

As noted by the Mayo Clinic, managing Meniere’s often involves dietary changes (like a low-salt diet) and medications to control the fluid buildup.

Vestibular Migraine: More Than a Headache

What it is: This is a type of migraine where vertigo or dizziness is a primary symptom.

It’s a neurological condition, not an inner ear problem, making it a form of central vertigo (though it can have features of both).

Many people with vestibular migraine do not experience a severe headache with every vertigo episode.

Key Symptoms: The vertigo episodes can last anywhere from a few minutes to several days. The sensation can be spinning vertigo, but it can also be a more general sense of dizziness, unsteadiness, and motion sensitivity.

It is often accompanied by other classic migraine symptoms, such as:

- Extreme sensitivity to light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia).

- Visual disturbances or aura (e.g., flashing lights, blind spots).

- Headache (though it may be mild or absent).

Connection: This condition directly addresses the common question about the link between vertigo and headaches. For many individuals, their “dizzy spells” are actually a manifestation of their underlying migraine disorder.

Less Common but Important Causes of Vertigo

To be truly comprehensive, it’s vital to acknowledge other potential causes.

While less frequent, identifying them is critical for proper treatment.

- Head or Neck Injury: Post-traumatic vertigo can result from damage to the inner ear or the brain pathways that control balance. Whiplash is a common trigger.

- Medication Side Effects: Certain drugs are known to be “ototoxic” (harmful to the ear). These include some powerful antibiotics (like gentamicin), high-dose aspirin, certain chemotherapy agents, and some anti-seizure medications.

- Acoustic Neuroma: This is a rare, non-cancerous (benign) tumor that grows on the main nerve leading from the inner ear to the brain (the vestibulocochlear nerve). As it grows, it can cause gradual hearing loss, tinnitus, and unsteadiness.

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS): As a central cause, MS can cause vertigo if it creates inflammatory lesions (demyelination) on the parts of the brainstem or cerebellum that control balance.

- Stroke or TIA (Transient Ischemic Attack): This is the most critical central cause to rule out. A stroke affecting the cerebellum or brainstem can cause sudden, persistent vertigo. It is almost always accompanied by other neurological signs (the “5 D’s” discussed later).

- Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD): This is a chronic condition characterized by a persistent sensation of unsteadiness or non-spinning dizziness that lasts for three months or more. It often begins after an acute vertigo event (like vestibular neuritis or BPPV) or a period of high stress. The brain fails to re-adapt, leading to a hypersensitivity to motion and complex visual environments.

How Do Doctors Pinpoint the Cause of Vertigo?

A correct diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective vertigo treatment.

Because so many conditions can cause it, a doctor’s approach is systematic, moving from the patient’s story to physical exams and, if necessary, advanced testing.

This process is designed to first rule out serious central causes and then identify the specific peripheral cause.

Step 1: The Patient History

This is the most important part of the evaluation.

Your doctor will ask detailed questions to understand the character of your vertigo. Be prepared to describe:

- Timing: How long do the episodes last (seconds, minutes, hours, or days)? Are they constant or intermittent?

- Triggers: What brings on the vertigo? Is it a change in head position, or does it happen spontaneously?

- Symptoms: Are you experiencing true spinning (vertigo) or just lightheadedness? Do you have hearing loss, tinnitus, headache, or any neurological symptoms?

- Context: Did the symptoms start after a head injury, a recent illness, or a new medication?

Step 2: The Physical Examination

Based on your history, your doctor will perform specific bedside tests to observe your vestibular system in action.

- Dix-Hallpike Maneuver: This is the gold-standard test for diagnosing BPPV. Your doctor will have you sit on an exam table, turn your head to one side, and then quickly lie you down with your head hanging slightly off the edge. If you have BPPV in the tested ear, this movement will trigger a brief episode of vertigo and a characteristic jerking eye movement called nystagmus, which the doctor will observe.

- Head Impulse Test: This test helps differentiate between a peripheral cause (like vestibular neuritis) and a central cause (like a stroke). The doctor will ask you to keep your eyes fixed on their nose while they make small, rapid turns of your head. Your ability (or inability) to keep your eyes stable provides clues about the health of your vestibular nerve.

- Balance and Gait Tests: You may be asked to walk heel-to-toe or stand with your feet together and eyes closed (Romberg’s test). Difficulty with these tasks can indicate a problem with your balance system.

Step 3: Further Testing (When Needed)

If the cause is not clear from the history and physical exam, or if a central cause is suspected, more advanced tests may be ordered.

- Hearing Tests (Audiometry): A formal hearing test is essential if you report hearing loss or tinnitus. It can help confirm a diagnosis of Meniere’s disease or labyrinthitis.

- Electronystagmography (ENG) or Videonystagmography (VNG): These tests measure involuntary eye movements (nystagmus) more precisely. Electrodes (ENG) or small cameras in goggles (VNG) are used to track your eye movements as you follow visual targets or as warm and cool water or air is circulated in your ear canals to stimulate the inner ear.

- MRI or CT Scans: Imaging of the brain is crucial if a central cause like a stroke, tumor, or multiple sclerosis is suspected. An MRI is particularly useful for visualizing the brainstem and cerebellum.

How Can You Get Rid of Vertigo? A Guide to Treatments

The answer to “how to get rid of vertigo” depends entirely on the underlying cause.

Treatment is not one-size-fits-all. It ranges from simple physical maneuvers to long-term rehabilitation and medication.

Canalith Repositioning Maneuvers (for BPPV)

For BPPV, the most common cause of vertigo, the treatment is remarkably effective and non-invasive.

- The Epley Maneuver: This is the gold-standard treatment for the most common form of BPPV (posterior canal). It involves a series of four specific head and body movements performed by a trained professional (like a doctor or physical therapist). The goal is to use gravity to guide the loose otoconia crystals out of the semicircular canal and back to the utricle, where they belong.

- Effectiveness: The Epley maneuver is highly successful. Research, including studies cited by institutions like the Cleveland Clinic, shows an immediate resolution rate of about 80-90% after a single application.

- Other Maneuvers: For less common forms of BPPV or if the Epley isn’t effective, other maneuvers like the Semont maneuver or the Foster maneuver (Half-Somersault) may be used.

Important Note: While videos online show how to perform these maneuvers at home, it is highly recommended to have the first treatment done by a professional.

They can confirm the diagnosis, ensure the maneuver is done correctly, and teach you a safe self-treatment version if your BPPV recurs.

Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT)

What it is: VRT is a specialized form of physical therapy. It’s an exercise-based program designed to “retrain” the brain to compensate for deficits in the inner ear system.

The brain has a remarkable ability, known as neuroplasticity, to adapt to faulty vestibular signals.

Who it helps: VRT is particularly effective for conditions that cause a persistent sense of imbalance or dizziness after the acute vertigo has passed, such as in cases of vestibular neuritis, post-concussion syndrome, or PPPD.

It is not a primary treatment for active BPPV or Meniere’s attacks.

Types of Exercises: A vestibular therapist will design a personalized program that may include:

- Gaze Stabilization: Exercises to improve control of eye movements so vision can be clear during head movement.

- Habituation: Repeated exposure to specific movements or visual stimuli that provoke dizziness, in order to decrease the brain’s sensitivity to them over time.

- Balance Training: Exercises to improve steadiness and coordination while standing and walking.

Medications for Vertigo

Medication plays a role in managing vertigo, but its use must be strategic.

- Symptom Relief (Short-Term): During a severe, acute attack of vertigo (like from vestibular neuritis), doctors may prescribe medications like Meclizine (Antivert), Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine), or benzodiazepines. Crucially, these medications only mask the symptoms of nausea and spinning. They do not treat the underlying cause and can hinder the brain’s ability to compensate if used long-term. They are typically recommended for no more than a few days.

- Treating the Cause: More targeted medications are used for specific conditions. This can include diuretics (“water pills”) to reduce fluid pressure in Meniere’s disease, corticosteroids to reduce inflammation in vestibular neuritis, or migraine-prevention medications (like beta-blockers or certain antidepressants) for vestibular migraine.

At-Home Management and Lifestyle Adjustments

While professional treatment is key, there are things you can do to manage symptoms and improve your quality of life.

- During an Attack: Find a safe position. Lie still in a dark, quiet room to reduce sensory input. Focus on a fixed point. Stay hydrated, especially if you are vomiting. Avoid sudden movements, bright lights, or reading.

- Lifestyle Triggers: Identifying and managing triggers is vital. This may include reducing stress, ensuring adequate sleep, staying well-hydrated, and avoiding excessive caffeine or alcohol. For those with Meniere’s disease, a low-sodium diet is often a key part of management.

- Safety at Home: Fall prevention is paramount. Remove tripping hazards like loose rugs, ensure good lighting throughout the house (especially at night), and install grab bars in the bathroom if needed.

When Should You Worry? Recognizing Red Flags

While most vertigo is caused by benign inner ear issues, it can occasionally be a sign of a medical emergency.

Knowing the difference can be life-saving.

See a Doctor If:

- Your vertigo is recurrent, severe, or prolonged and has not been diagnosed.

- It is accompanied by new hearing loss or significant tinnitus.

- It does not improve or changes in character.

Emergency: Go to the ER or Call 911 Immediately

If vertigo appears suddenly and is accompanied by any of the following neurological symptoms, it could be a sign of a stroke or another serious central nervous system problem. Think of the “5 D’s” and other key signs:

- Diplopia: Double vision or sudden vision loss.

- Dysarthria: Slurred or difficult speech.

- Dysphagia: Trouble swallowing.

- Dysmetria: Incoordination, such as being unable to walk a straight line, or clumsiness in the arms or legs.

- Dropping: Sudden weakness or numbness in the face, arms, or legs, especially on one side of the body.

Also seek immediate care for vertigo accompanied by:

- A new, different, or “thunderclap” severe headache.

- Fever and a stiff neck.

- Loss of consciousness.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How long does vertigo typically last?

It varies by cause. BPPV episodes last under a minute. An attack from vestibular neuritis can last for days, while Meniere’s disease episodes can last for hours. Chronic conditions like PPPD can cause persistent feelings of unsteadiness for months.

2. Can stress or anxiety cause vertigo?

While anxiety doesn’t directly cause true rotational vertigo, it can cause feelings of dizziness and lightheadedness. More importantly, high stress and anxiety can trigger or worsen episodes of underlying vestibular conditions like Meniere’s disease and vestibular migraine.

3. Is vertigo hereditary?

Generally, no. However, some conditions that cause vertigo have a genetic component. Vestibular migraine, for example, often runs in families. Some rare forms of familial benign recurrent vertigo have also been identified, but this is not common.

4. Can vertigo be a sign of a heart problem?

Usually not. Vertigo is a spinning sensation from the vestibular system. Dizziness or lightheadedness (feeling faint) can be a sign of a heart problem, like an arrhythmia or low blood pressure, which reduces blood flow to the brain.

5. What is the fastest way to cure BPPV at home?

The fastest, most effective treatment is a canalith repositioning maneuver like the Epley. While it’s best to have a professional perform it first, they can teach you a self-treatment version for rapid relief if symptoms recur at home.

6. Can dehydration cause vertigo?

Dehydration can cause dizziness, lightheadedness, and unsteadiness due to a drop in blood pressure and reduced blood flow to the brain. While it doesn’t typically cause true rotational vertigo, it can worsen symptoms in someone with an existing vestibular disorder.

7. Why do I get vertigo when I lie down?

Vertigo triggered by lying down, rolling over in bed, or sitting up is the classic sign of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). The change in head position relative to gravity causes loose inner ear crystals to move, triggering the spinning sensation.

8. Is it safe to drive with vertigo?

No. It is not safe to drive if you are experiencing active vertigo or have a condition that causes sudden, unpredictable attacks. The loss of balance and spatial orientation makes operating a vehicle extremely dangerous. Consult your doctor about when it is safe to resume driving.

Conclusion

Vertigo can be a profoundly disruptive and frightening experience, but it is almost always a treatable symptom.

The key takeaway is that an accurate diagnosis is paramount.

Understanding whether your vertigo stems from a simple mechanical issue like BPPV, an inflammatory condition like vestibular neuritis, or a more complex disorder like Meniere’s disease is the only way to find the right path to relief.

While the spinning sensation can make you feel powerless, knowledge is your first tool for taking back control.

By recognizing your specific symptoms, understanding the potential causes, and knowing when to seek help, you can become an active partner in your own recovery.

If you are experiencing recurrent or severe vertigo, don’t self-diagnose or ignore it. Schedule an appointment with your healthcare provider, an ENT (otolaryngologist), or a neurologist.

They have the expertise to perform a thorough evaluation, provide a definitive diagnosis, and guide you toward a personalized and effective treatment plan.

Share your experience with vertigo in the comments below. Your story, questions, or coping strategies could provide invaluable support and insight to someone else on their journey to recovery.