Osteoporosis is a medical condition that weakens bones, making them fragile and more likely to break.

This progressive disease develops silently over many years, often without any symptoms until a minor fall or even a simple cough causes a fracture.

Affecting over 500 million people worldwide, according to the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), it represents a major global health crisis, particularly among aging populations.

This comprehensive guide will delve into every aspect of osteoporosis, from its hidden causes and subtle symptoms to the most advanced diagnostic tools and treatments available today.

You will learn not only how to manage the condition but also how to build a strong foundation for lifelong bone health.

In This Article

What is Osteoporosis? A Deeper Look at Bone Health

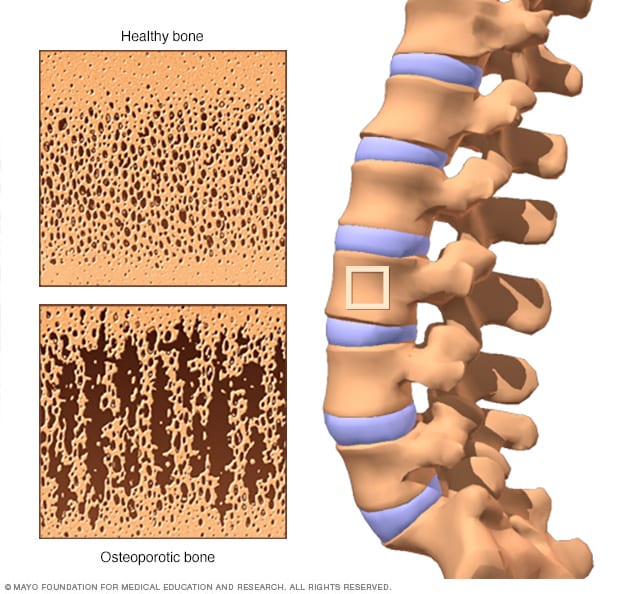

At its core, osteoporosis is a disease defined by reduced bone mass and the deterioration of bone tissue’s internal structure, or microarchitecture. The name itself, derived from Latin, means “porous bones”.

To understand this, it’s helpful to visualize healthy bone under a microscope. It resembles a dense, strong honeycomb matrix.

In a person with osteoporosis, the “holes” in this honeycomb become much larger, weakening the bone from the inside out.

Under a microscope, healthy bone (top) has a dense honeycomb appearance. Osteoporotic bone (bottom) is far more porous and fragile.

The Constant Cycle of Bone Remodeling

Bone is not a static, lifeless material, it is a dynamic, living tissue that is constantly undergoing a process called bone remodeling. This lifelong cycle involves two key types of cells:

- Osteoclasts: These cells are responsible for breaking down and removing old, worn-out bone tissue (a process called resorption).

- Osteoblasts: These cells are responsible for building new bone tissue to replace what was removed.

In childhood and early adulthood, bone formation by osteoblasts outpaces bone resorption by osteoclasts.

This allows the skeleton to grow in size and density. We reach our peak bone mass—the maximum amount of bone tissue we will ever have—by around age 30. Think of this as your “bone bank account”.

A higher peak bone mass means you have more bone in reserve for later in life.

After age 35, this balance shifts. The rate of bone breakdown gradually begins to exceed the rate of bone formation.

Osteoporosis occurs when this imbalance becomes significant, leading to a rapid decline in bone density and strength.

Why is Osteoporosis Called the ‘Silent Disease’? (Symptoms)

Osteoporosis earns its nickname as the “silent disease” because there are typically no noticeable symptoms in the early stages of bone loss. Many people are completely unaware they have the condition until a bone breaks unexpectedly.

However, as the disease progresses and bones become significantly weakened, certain signs and symptoms may appear.

Late-Stage Osteoporosis Symptoms

- Fractures from minor incidents: A bone that breaks much more easily than expected is the hallmark sign. These fragility fractures can occur from a simple fall from standing height, or even from mild stresses like bending over, lifting a bag of groceries, or a strong cough or sneeze. The most common sites for osteoporosis-related fractures are the hip, wrist and spine.

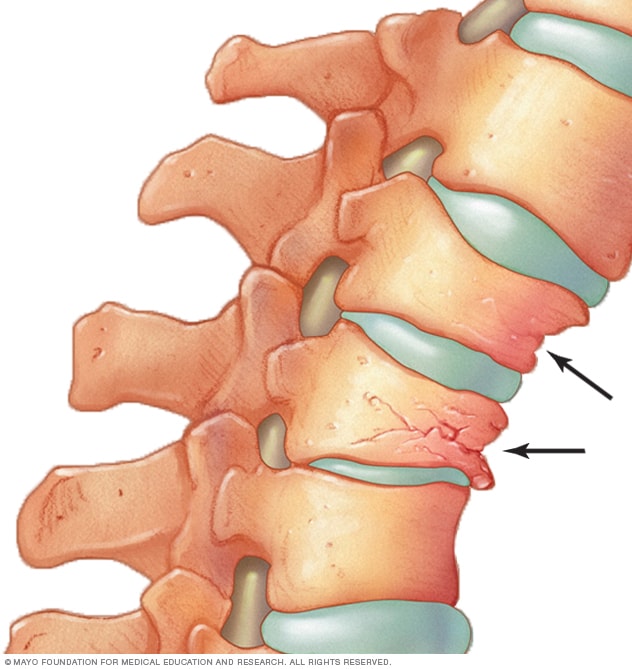

- Back pain: This can be caused by a fractured or collapsed vertebra in the spine. The pain can be sudden and severe or a dull, chronic ache.

- Loss of height over time: As vertebrae in the spine weaken and collapse (known as compression fractures), a person can gradually become shorter, sometimes losing an inch or more in height.

- A stooped or curved posture: The collapse of spinal vertebrae can lead to a curving of the upper back, a condition known as kyphosis, often referred to as a “dowager’s hump”.

- Shortness of breath: In severe cases, multiple vertebral compression fractures can reduce the space in the chest cavity, compressing the lungs and making it difficult to breathe deeply.

Compression fractures occur when vertebrae weaken and collapse, leading to pain, height loss and a hunched posture.

When to See a Doctor About Osteoporosis

Because early detection is crucial, you should talk to your healthcare provider about your risk for osteoporosis if you:

- Went through menopause early (before age 45).

- Have taken corticosteroid medications (like prednisone) for several months at a time.

- Have a parent or sibling who has been diagnosed with osteoporosis or experienced a hip fracture.

- Have experienced a fracture after the age of 50 from a minor injury.

Who is at Risk? Unpacking the Causes and Risk Factors

A combination of genetic, lifestyle and medical factors determines your likelihood of developing osteoporosis. Some of these you cannot change, while others are within your control.

Unchangeable Risk Factors

- Sex: Women are much more likely to develop osteoporosis than men. They tend to have smaller, thinner bones and experience a rapid drop in bone-protecting estrogen during menopause. However, as noted in a 2025 study, the disease is increasingly recognized and often underdiagnosed in men.

- Age: The older you get, the greater your risk of osteoporosis. Bone loss accelerates with age.

- Race: You’re at the greatest risk if you are of White or Asian descent.

- Family History: Having a parent or sibling with osteoporosis, especially if a parent fractured a hip, puts you at a significantly higher risk.

- Body Frame Size: Individuals with small body frames tend to have a higher risk because they may have less bone mass to draw from as they age.

- Genetics: Specific genes, such as variants in the LRP5 gene, play a critical role in the Wnt signaling pathway, which is essential for bone formation. Mutations in this gene can lead to severe, early-onset osteoporosis, as described in case studies published in PMC.

Hormonal Factors

Hormone levels are a major determinant of bone health.

- Sex Hormones: The sharp decline in estrogen levels at menopause is one of the strongest risk factors for osteoporosis in women. In men, low testosterone levels can also contribute to bone loss. Treatments for prostate and breast cancer that reduce testosterone and estrogen, respectively, can accelerate this process.

- Thyroid Hormone: Too much thyroid hormone, either from an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) or from taking excessive thyroid hormone medication, can cause bone loss.

- Other Glands: Overactive parathyroid and adrenal glands can also lead to osteoporosis by disrupting the body’s calcium balance.

Dietary and Lifestyle Choices

- Low Calcium Intake: A lifelong lack of calcium plays a crucial role in the development of osteoporosis. Calcium is the primary building block of bone.

- Low Vitamin D Intake: Vitamin D is essential for your body to absorb calcium. Insufficient levels, common in many populations, severely hamper bone health.

- Eating Disorders: Severely restricting food intake, as seen in anorexia nervosa, weakens bones. Studies have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 are linked to decreased bone density in these patients.

- Sedentary Lifestyle: “Use it or lose it” applies to bones. Weight-bearing exercises (like walking, jogging and weightlifting) stimulate bone-building cells. A lack of physical activity increases the risk of osteoporosis.

- Excessive Alcohol Consumption: Regularly consuming more than two alcoholic drinks a day increases your risk.

- Tobacco Use: Smoking is toxic to bone-building cells (osteoblasts) and has been shown to contribute to weaker bones.

Medical Conditions and Medications

Medications that Harm Bones

Long-term use of certain medications can interfere with the bone remodeling process.

The most well-known are corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone, cortisone), often used to treat inflammatory conditions like asthma and rheumatoid arthritis.

These drugs can decrease calcium absorption and increase bone breakdown. Other medications associated with bone loss include some used to treat seizures, gastric reflux (proton pump inhibitors), cancer and transplant rejection.

Diseases Linked to Osteoporosis

The risk of osteoporosis is higher in people with certain medical problems, including:

- Autoimmune disorders like Rheumatoid Arthritis and Lupus.

- Digestive and gastrointestinal disorders like Celiac disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), which can impair nutrient absorption.

- Kidney or liver disease.

- Cancers like multiple myeloma.

- Diabetes: This presents a complex picture known as the “diabetic bone paradox”. While individuals with Type 2 diabetes often have normal or even higher bone mineral density (BMD), they paradoxically face an increased risk of fractures. Research suggests this is due to poor bone quality and alterations in the bone’s microarchitecture, not a lack of density .

New and Emerging Risk Factors: Microplastics

A growing body of research is uncovering a disturbing new threat to bone health: microplastics.

A 2025 review of scientific articles found that these tiny plastic particles can infiltrate bone tissue. In vitro studies have shown that microplastics can:

- Promote inflammation.

- Accelerate cellular aging.

- Impair the function of bone marrow stem cells.

- Favor the formation of osteoclasts, the cells that break down bone.

This emerging field suggests that environmental pollution may be a previously unrecognized contributor to the global osteoporosis epidemic.

How is Osteoporosis Diagnosed?

Since osteoporosis is a silent disease, diagnosis often relies on proactive screening.

The gold standard for measuring bone strength and diagnosing osteoporosis is the Bone Mineral Density (BMD) test, most commonly performed using a technique called Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA or DXA).

A DEXA scan is a quick, painless, and non-invasive procedure that measures bone density in key areas like the hip and spine.

The DEXA Scan Explained

A DEXA scan is a simple, quick (10-15 minutes), and painless procedure. You lie on a padded table while a scanner passes over your body.

It uses very low levels of X-rays to measure the mineral content of your bones, typically at the hip and lumbar spine. The radiation exposure is minimal, less than that of a standard chest X-ray.

Understanding Your T-Score

The results of a DEXA scan are reported as a “T-score”. This score compares your bone density to that of a healthy 30-year-old adult of the same sex.

- T-score of -1.0 or above: Normal bone density.

- T-score between -1.0 and -2.5: Low bone mass, a condition called osteopenia. This is a precursor to osteoporosis.

- T-score of -2.5 or below: Diagnosis of osteoporosis.

A “Z-score” may also be reported, which compares your bone density to the average for your age, sex and ethnicity.

A very low Z-score can suggest that something other than aging is causing bone loss.

Who Should Get a Bone Density Test?

Screening is generally recommended for:

- All women aged 65 and older.

- All men aged 70 and older.

- Postmenopausal women under 65 with risk factors.

- Men aged 50-69 with risk factors.

- Anyone over 50 who has broken a bone.

- Anyone with a medical condition or taking a medication associated with bone loss.

Other Diagnostic Tools

While DEXA is the standard, other tools can help assess fracture risk:

- FRAX® (Fracture Risk Assessment Tool): Developed by the World Health Organization, this online tool calculates your 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (hip, spine, forearm, shoulder) based on your BMD and other key risk factors.

- Quantitative Ultrasound (QUS): This portable screening tool often measures the heel bone to estimate fracture risk. It is not as precise as DEXA for diagnosis but can identify individuals who may need further testing.

What are the Treatments for Osteoporosis?

Treating osteoporosis involves a multi-faceted approach aimed at slowing bone loss, building new bone, and, most importantly, preventing fractures.

Treatment plans are highly individualized and combine lifestyle modifications with medication.

Lifestyle and Nutrition: The Foundation of Treatment

1. Calcium and Vitamin D

These two nutrients are the cornerstone of bone health. Your body cannot build strong bones without them.

- Calcium: Adults aged 19-50 need 1.000 mg per day. Women over 50 and men over 70 should aim for 1.200 mg per day. Excellent dietary sources include low-fat dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese), dark green leafy vegetables (kale, broccoli), canned salmon or sardines with bones and fortified foods like orange juice and cereals.

- Vitamin D: This vitamin is crucial for calcium absorption. Most adults need 600-800 International Units (IU) per day, with some needing more. While sunlight helps the body produce Vitamin D, dietary sources (fatty fish, fortified milk) and supplements are often necessary, especially for those in northern latitudes or with limited sun exposure.

“For most with osteoporosis or osteopenia, the goal will be around 1.200 milligrams of calcium. The problem is, the average dietary calcium intake for people 50 years of age or older is half of what’s recommended”. – Matthew T. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., Mayo Clinic.

2. Protein and Other Nutrients

Protein is a key component of bone tissue. Ensuring adequate protein intake is important for maintaining bone strength.

Other minerals like magnesium, phosphorus and vitamin K also play supporting roles in bone metabolism.

3. Exercise for Stronger Bones

Exercise is a powerful tool against osteoporosis. A well-rounded program should include:

- Weight-Bearing Exercises: Activities that make you move against gravity, like walking, jogging, dancing and stair climbing. These directly stimulate the bones in your legs, hips and lower spine.

- Resistance/Strength Training: Using weights, resistance bands, or your own body weight to strengthen muscles and bones, particularly in the arms and upper spine.

- Balance and Posture Exercises: Activities like Tai Chi and yoga can improve stability and coordination, reducing the risk of falls.

Medications for Osteoporosis

For those with a diagnosis of osteoporosis or at high risk of fracture, medication is often necessary.

These drugs work by either slowing bone breakdown or stimulating bone formation.

| Medication Class | How It Works | Examples | Administration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphosphonates | Slows down osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells). The most common first-line treatment. | Alendronate (Fosamax), Risedronate (Actonel), Ibandronate (Boniva), Zoledronic acid (Reclast) | Oral (daily, weekly, or monthly) or IV infusion (yearly) | Must be taken on an empty stomach with a full glass of water, patient must remain upright for 30-60 mins. |

| RANKL Inhibitor | Blocks a key protein (RANKL) involved in osteoclast formation and activation. | Denosumab (Prolia) | Subcutaneous injection every 6 months | Effects wear off quickly if stopped, must transition to another medication to prevent rapid bone loss. |

| Hormone-Related Therapy | Mimics estrogen’s bone-protective effects or provides hormone replacement. | Estrogen therapy, Raloxifene (Evista) | Oral pill or patch | Used in specific populations (e.g., younger postmenopausal women) due to other health risks/benefits. |

| Anabolic Agents | Stimulates osteoblasts to build new bone. | Teriparatide (Forteo), Abaloparatide (Tymlos) | Daily subcutaneous injection | Reserved for severe osteoporosis, treatment is typically limited to 2 years. |

| Sclerostin Inhibitor (Dual-Action) | Blocks the protein sclerostin, which both increases bone formation and decreases bone resorption. | Romosozumab (Evenity) | Monthly subcutaneous injections for 12 months | A powerful, newer option for very high-risk patients. Must be followed by an anti-resorptive agent. |

Advanced Treatment: Romosozumab (Evenity)

One of the most significant recent advances in osteoporosis treatment is romosozumab.

This medication represents a unique, dual-action approach. It is a monoclonal antibody that targets and inhibits a protein called sclerostin. Sclerostin naturally puts the brakes on bone formation.

By blocking it, romosozumab “releases the brakes”, leading to a rapid increase in bone formation while also modestly decreasing bone resorption.

As described in a review by StatPearls, this dual effect makes it a highly effective treatment for patients with severe osteoporosis and a very high risk of fracture.

Treatment is limited to 12 monthly injections and must be followed by a medication that slows bone breakdown, like a bisphosphonate or denosumab, to lock in the gains.

Surgical Procedures for Spinal Fractures

For patients suffering from painful vertebral compression fractures, two minimally invasive procedures may be considered:

- Vertebroplasty: Involves injecting a medical-grade bone cement directly into the fractured vertebra to stabilize it and relieve pain.

- Kyphoplasty: A balloon is first inserted into the fractured vertebra and inflated to restore some of its height. The balloon is then removed, and the created cavity is filled with bone cement. This can help correct spinal deformity in addition to relieving pain.

What are the Complications of Osteoporosis?

The consequences of osteoporosis extend far beyond the broken bones themselves.

The complications can be life-altering and, in some cases, life-threatening.

- Fractures: This is the most direct and serious complication. Hip fractures are particularly devastating. According to data, mortality rates after a hip fracture can be as high as 20% within the first year due to complications like blood clots, pneumonia and infections from prolonged immobility.

- Chronic Pain: Multiple vertebral fractures can lead to persistent, debilitating back pain that is difficult to manage.

- Loss of Independence: A hip fracture often results in a permanent loss of mobility. Many patients are no longer able to live independently and require long-term nursing care. This loss of autonomy can be profoundly distressing.

- Psychological Impact: The fear of falling and sustaining another fracture can lead to anxiety, social isolation and depression. Patients may limit their activities, leading to a downward spiral of physical deconditioning and reduced quality of life.

“Individuals who have osteoporosis can indeed develop depression… In most cases, this occurs due to the constant fear of pain and fracture. The patient begins to limit their activities more and more, until depressive symptoms appear”. – Gualter Maldonado, Orthopedist

Can Osteoporosis be Prevented?

Yes, to a large extent, osteoporosis is a preventable disease.

The key is to focus on building the strongest bones possible during your youth and then taking steps to maintain that bone mass throughout your life.

Building Your “Bone Bank” in Youth

Childhood, adolescence and early adulthood are critical windows for bone development. About 90% of peak bone mass is acquired by age 18 in girls and age 20 in boys.

Maximizing this peak bone mass is the best defense against osteoporosis later in life. This involves:

- Adequate Nutrition: Ensuring a diet rich in calcium and vitamin D.

- Regular Exercise: Participating in high-impact and weight-bearing activities like running, gymnastics and team sports.

- Avoiding Negative Factors: Steering clear of smoking and excessive alcohol.

Maintaining Bone Health in Adulthood

The same strategies that build strong bones in youth help maintain them in adulthood:

- Get Enough Calcium and Vitamin D: Meet the daily recommended intakes through diet and, if necessary, supplements.

- Engage in Regular Weight-Bearing Exercise: Aim for at least 30 minutes most days of the week.

- Incorporate Strength Training: Lift weights or use resistance bands 2-3 times per week.

- Don’t Smoke and Limit Alcohol: Avoid tobacco and keep alcohol consumption moderate.

- Prevent Falls: As you get older, take steps to make your home safer to reduce the risk of falls.

Living with Osteoporosis: A Practical Guide

A diagnosis of osteoporosis requires a proactive approach to daily life to minimize fracture risk and maintain quality of life.

Fall Prevention is Fracture Prevention

Since most fractures in people with osteoporosis are caused by falls, creating a safe environment is paramount.

- Home Safety Check: Remove tripping hazards like loose rugs and electrical cords. Ensure all areas are well-lit, especially stairs and hallways. Install grab bars in the bathroom and handrails on all staircases.

- Mindful Movement: Wear sturdy, low-heeled shoes with good traction. Be cautious on wet or icy surfaces. Use a cane or walker for stability if needed.

- Check Your Vision: Have your eyes checked regularly. Poor vision increases the risk of falls.

- Review Medications: Ask your doctor or pharmacist if any of your medications can cause dizziness or drowsiness.

Managing Pain and Daily Activities

For those with painful spinal fractures, a physical therapist can be an invaluable resource. They can teach you:

- Proper body mechanics for lifting, bending, and daily tasks to avoid stressing your spine.

- Exercises to strengthen your core and back muscles to better support your spine.

- Pain management techniques, including heat, ice and gentle stretching.

Special Populations: Osteoporosis Beyond Postmenopausal Women

While osteoporosis is most common in postmenopausal women, it is not exclusive to this group.

Understanding its impact on other populations is crucial.

Osteoporosis in Men

Osteoporosis in men is a significant but often overlooked health problem.

The IOF estimates that 1 in 5 men over age 50 will experience an osteoporotic fracture. Men are often diagnosed later than women, frequently only after they have already sustained a fracture.

The mortality rate for men after a hip fracture is even higher than for women. Risk factors are similar, with low testosterone (hypogonadism), smoking and excessive alcohol use being major contributors.

Osteoporosis in Children and Adolescents

While rare, osteoporosis can occur in children, usually due to an underlying medical condition (like juvenile arthritis or celiac disease) or long-term use of medications like corticosteroids.

This is known as secondary osteoporosis. More commonly, the focus in this age group is on identifying and addressing risk factors that could lead to a lower peak bone mass, setting the stage for osteoporosis in adulthood.

The Future of Osteoporosis Care

The field of osteometabolic health is rapidly evolving, with exciting advancements in research and technology promising better ways to diagnose, treat and monitor osteoporosis.

Emerging Research and Therapies

Scientists are continually exploring the complex biology of bone. Recent research published in Nature has identified a new hormone, CCN3, that appears to play a role in building strong bones, potentially opening the door for entirely new classes of anabolic drugs.

Genetic research into pathways like Wnt signaling and genes like LRP5 and SOST continues to yield novel drug targets, like romosozumab.

The Role of Technology and Telemedicine

Technology is transforming how chronic diseases are managed. For osteoporosis, this includes:

- AI-Powered Diagnostics: Researchers are developing machine learning algorithms, like the Osseus method in Brazil, to analyze medical images or patient data to predict fracture risk more accurately and identify candidates for DEXA screening .

- Remote Patient Monitoring: Wearable sensors can track activity levels and even detect falls, alerting caregivers or healthcare providers.

- Telemedicine: Virtual consultations allow for more frequent and convenient follow-ups with specialists, improving treatment adherence and management, especially for patients in rural areas or with limited mobility.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can osteoporosis be reversed?

While you can’t completely reverse bone loss to the levels of a young adult, treatments can significantly increase bone density and strength. Anabolic medications like teriparatide and romosozumab actively build new bone, effectively reversing some of the damage and substantially reducing fracture risk.

2. Is osteopenia the same as osteoporosis?

No. Osteopenia is a condition of low bone mass that is less severe than osteoporosis. It’s considered a warning sign or a precursor. Not everyone with osteopenia will develop osteoporosis, but it does place you at a higher risk for fractures.

3. How painful is osteoporosis?

The condition of having low bone density itself is not painful. The pain associated with osteoporosis comes from the fractures it causes. A sudden, severe back pain could indicate a spinal compression fracture, which can lead to chronic pain if not managed properly.

4. Can men get osteoporosis?

Yes, absolutely. While more common in women, millions of men have osteoporosis. It is often underdiagnosed in men, who may only discover they have it after a fracture. Men also have a higher mortality rate following a hip fracture compared to women.

5. What is the single best exercise for osteoporosis?

There isn’t one single “best” exercise. The ideal routine combines weight-bearing activities (like brisk walking), resistance training (like lifting weights), and balance exercises (like Tai Chi). This combination addresses bone density, muscle strength and fall prevention simultaneously.

6. Does osteoporosis shorten your life?

Osteoporosis itself is not fatal. However, the fractures it causes, particularly hip fractures, can lead to complications that significantly increase the risk of death within a year. Preventing fractures is key to maintaining both lifespan and quality of life.

7. Can you feel your bones getting weaker?

No, you cannot feel your bones losing density. This is why osteoporosis is called a “silent disease”. The first feeling associated with it is often the acute pain of an unexpected fracture. This is why screening for at-risk individuals is so important.

8. What’s the difference between a T-score and a Z-score?

A T-score compares your bone density to that of a healthy young adult, and it is used to diagnose osteoporosis. A Z-score compares your bone density to people of your own age and sex, and it is useful for identifying potential secondary causes of bone loss.

Take Control of Your Bone Health Today

Osteoporosis is a serious condition, but it is not an inevitable part of aging.

From building a strong “bone bank” in your youth to adopting a bone-healthy lifestyle and utilizing advanced medical treatments in later life, there are powerful steps you can take at every age to protect your skeleton.

Understanding your personal risk factors, engaging in regular exercise, ensuring proper nutrition, and working with your healthcare provider are the keys to preventing this silent disease from compromising your health and independence.

If you are over 50 or have risk factors, don’t wait for a fracture to be your first symptom. Talk to your doctor about a bone density test. It’s a simple, painless step that could save you from a world of pain and disability.

Share this article with friends and family to spread awareness about this critical health issue. What steps will you take for your bone health today? Let us know in the comments below!

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The information contained herein is not a substitute for, and should never be relied upon for, professional medical advice.

Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.