An autoimmune disease is a condition where your body’s immune system, designed to be a defender, mistakenly attacks its own healthy cells and tissues.

This internal confusion is more common than many realize. While estimates vary, recent large-scale studies suggest that autoimmune diseases affect up to 1 in 10 people, and their prevalence is alarmingly on the rise globally.

Research published in PubMed Central indicates yearly increases in worldwide incidence and prevalence are as high as 19.1% and 12.5%, respectively, signaling a growing public health challenge (Miller et al., 2022).

In this comprehensive guide, we will demystify these complex conditions.

We’ll explore what an autoimmune disease is, delve into the 10 most common types, and discuss the latest breakthroughs in diagnosis and treatment that are offering new hope.

Whether you’re seeking answers for yourself or a loved one, this guide provides the clear, authoritative information you need.

In This Article

What Exactly Is an Autoimmune Disease?

At its core, an autoimmune disease represents a fundamental failure of the immune system’s self-tolerance.

To understand this, it helps to use a simple analogy.

Think of your immune system as your body’s highly sophisticated internal security force.

Its primary job is to identify and eliminate foreign invaders like viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites—the “foes”. It has a complex system of checks and balances to ensure it can distinguish these threats from your own healthy cells and tissues—the “friends”.

In an autoimmune disease, this recognition system fails. The security force becomes confused and begins to launch a sustained attack against the very body it’s supposed to protect. – Based on information from Cleveland Clinic

This friendly fire is not random.

The immune system’s T-cells and B-cells, which normally lead the charge against pathogens, malfunction.

They start producing proteins called autoantibodies that target specific healthy tissues.

The nature of the attack determines the type of autoimmune disease.

These conditions can be broadly categorized into two types:

- Organ-specific autoimmune disease: The immune attack is directed against a single organ. A classic example is Type 1 Diabetes, where the immune system specifically targets and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells within the pancreas.

- Systemic autoimmune disease: The immune attack is widespread and can affect multiple organs and tissues throughout the body. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Lupus) is a prime example, capable of causing inflammation in the joints, skin, kidneys, brain, and more.

The scope of this problem is vast.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) reports that researchers have identified between 80 and 150 distinct autoimmune diseases.

While each has unique characteristics, many share overlapping symptoms like chronic fatigue and inflammation, which often makes diagnosis a complex and lengthy process.

Why Are Autoimmune Diseases Becoming More Common?

The rising prevalence of autoimmune conditions is a significant concern for global health organizations.

Epidemiologic studies from around the world have confirmed a consistent upward trend that cannot be explained by improved diagnostic methods alone (Miller et al., 2022).

For instance, the incidence of Type 1 Diabetes has been increasing by 3-4% annually for the past three decades.

This points to a genuine increase in the number of people developing these conditions.

Scientists believe the answer lies in a complex, multi-faceted interaction between our genes and the modern world.

The Genetic-Environmental Link: A “Two-Hit” Hypothesis

The prevailing scientific consensus is that an autoimmune disease rarely develops from a single cause.

Instead, it’s often the result of what’s known as the “two-hit” hypothesis.

- The First Hit (Genetic Predisposition): An individual inherits certain genes that make their immune system more susceptible to malfunction. Research has shown that autoimmune diseases often cluster in families, highlighting the importance of genetic factors (Pathogenesis of autoimmune disease). However, having these genes is not a guarantee of developing a disease.

- The Second Hit (Environmental Trigger): The genetically susceptible individual is then exposed to one or more environmental factors that “pull the trigger,” activating the faulty immune response.

Potential Environmental Triggers

Identifying these triggers is a major focus of current research.

While the exact mechanisms are still being unraveled, several key factors are implicated:

- Infections: A leading theory is that certain viral or bacterial infections can set off autoimmunity through a mechanism called “molecular mimicry”. A pathogen might have a protein that looks very similar to one of our own proteins. The immune system mounts an attack against the pathogen, but in the process, it mistakenly learns to attack the similar-looking “self” protein as well. Recent studies have explored SARS-CoV-2 as a potential trigger for some new-onset autoimmune diseases, although the risk may decrease over time with newer variants (New-onset autoimmune disease after COVID-19).

- Western Lifestyle Factors: The higher incidence of autoimmune disease in industrialized nations points towards elements of the modern lifestyle. This includes the “Western diet” (high in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats), chronic psychological stress, and exposure to a wide range of industrial chemicals and environmental toxins that were not present in our evolutionary past.

- The Hygiene Hypothesis: This theory proposes that our modern, sanitized environments may leave our immune systems “undertrained.” By having less exposure to a diverse range of microbes, parasites, and infections in early life, the immune system may not develop its regulatory pathways properly, making it more prone to overreacting to harmless substances or even our own tissues later in life.

What Are the General Symptoms of an Autoimmune Disease?

One of the greatest challenges in diagnosing an autoimmune disease is that the early symptoms are often nonspecific, vague, and can mimic other, more common ailments.

Many people suffer for years before receiving an accurate diagnosis.

While each disease has its unique profile, many share a common set of initial warning signs driven by systemic inflammation.

Common, early symptoms that could indicate an underlying autoimmune process include:

- Persistent, debilitating fatigue that is not relieved by rest or sleep

- Aching muscles and chronic joint pain, swelling, or stiffness

- Recurring low-grade fevers with no obvious cause

- Skin problems, such as rashes, redness, or sensitivity to sunlight (photosensitivity)

- Swollen lymph nodes (glands) in the neck, armpits, or groin

- Digestive issues like abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, or constipation

- Numbness or tingling in the hands and feet

- Difficulty concentrating or “brain fog“

The Cycle of Flares and Remission

A hallmark characteristic of many autoimmune diseases is their unpredictable course, often marked by a cycle of “flares” and “remission.”

- A flare is a period when the disease becomes active and symptoms suddenly worsen. Flares can be triggered by factors like stress, infection, or even sun exposure.

- Remission is a period when the symptoms subside or disappear entirely. The disease is still present, but it is inactive or under control.

This fluctuating pattern can be emotionally and physically draining, making it difficult to plan daily life.

The primary goal of treatment is to control flares and extend periods of remission for as long as possible.

The 10 Most Common Autoimmune Diseases Explained

While the list of known autoimmune conditions is long and growing, a relatively small number of them account for the vast majority of diagnoses.

Understanding these common diseases provides a clearer picture of how autoimmunity can manifest in the body.

Here, we break down the 10 most prevalent conditions, their specific targets, and key symptoms.

1. Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

What It Is: Rheumatoid Arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disorder where the immune system primarily attacks the synovium—the lining of the membranes that surround your joints. This attack causes the synovium to thicken, which can eventually destroy the cartilage and bone within the joint, leading to deformity and loss of function.

Specific Symptoms: The classic sign of RA is symmetrical inflammation in the joints, meaning if a joint in one hand is affected, the same joint in the other hand likely will be too. Key symptoms include tender, warm, swollen joints; severe joint stiffness that is typically worse in the mornings and after inactivity; and systemic symptoms like fatigue, fever, and loss of appetite.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical symptoms, a physical exam, and specific lab tests. Blood tests look for the presence of Rheumatoid Factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies, which are highly specific to RA. Imaging tests like X-rays and MRIs can assess the extent of joint damage.

At-Risk Groups: RA is significantly more common in women than men and typically begins in middle age, though it can occur at any age.

2. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

What It Is: Lupus is the quintessential systemic autoimmune disease, often called “the great imitator” because its symptoms can mimic so many other illnesses. In Lupus, the immune system produces autoantibodies that can attack virtually any part of the body, including the joints, skin, kidneys, blood cells, brain, heart, and lungs.

Specific Symptoms: Symptoms are highly variable and depend on which body systems are affected. A characteristic sign, though not present in all patients, is a butterfly-shaped rash (malar rash) that spreads across the cheeks and bridge of the nose. Other common symptoms include extreme fatigue, joint pain and swelling, fever, and photosensitivity. More severe complications can involve kidney inflammation (lupus nephritis), chest pain, and neurological issues.

Diagnosis: Diagnosing Lupus is a complex puzzle. Doctors often use a checklist of clinical and laboratory criteria. A positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test is a key finding, as it’s present in nearly all people with Lupus. However, a positive ANA alone is not a diagnosis, as it can be positive in other conditions.

Treatment Note: Lupus is at the forefront of research into new treatments. As we’ll discuss later, emerging options like CAR T-cell therapy are showing remarkable promise in clinical trials for severe, treatment-resistant Lupus (UC Davis Health).

3. Psoriasis / Psoriatic Arthritis

What It Is: Psoriasis is an autoimmune condition that dramatically speeds up the life cycle of skin cells. This causes cells to build up rapidly on the surface of the skin, forming thick, red, inflamed patches covered with silvery scales. In up to 30% of people with psoriasis, the condition evolves to include joint inflammation, a condition known as psoriatic arthritis.

Specific Symptoms: For psoriasis, the primary symptom is the presence of well-defined, raised, red plaques with silvery scales. These can be itchy or sore and can appear anywhere on the body. For psoriatic arthritis, symptoms include joint pain, stiffness, and swelling, which can affect any joint, including the fingertips and spine.

Diagnosis: Psoriasis is typically diagnosed by a dermatologist based on a clinical examination of the skin, scalp, and nails. If joint symptoms are present, a rheumatologist will make the diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis based on symptoms and imaging tests.

4. Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

What It Is: Multiple Sclerosis is an autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord. The immune system attacks the myelin sheath, the fatty, protective substance that covers nerve fibers. This damage disrupts or blocks the communication between the brain and the rest of the body, leading to a wide range of neurological symptoms.

Specific Symptoms: The symptoms of MS are notoriously unpredictable and vary greatly from person to person depending on the location and severity of nerve damage. Common symptoms include numbness or weakness in one or more limbs (often on one side of the body at a time), partial or complete loss of vision (usually in one eye at a time), prolonged double vision, tingling or pain, fatigue, dizziness, and problems with coordination and balance.

Diagnosis: There is no single test for MS. Diagnosis relies on ruling out other conditions and combining evidence from a neurological exam, MRI scans of the brain and spinal cord to detect characteristic lesions (areas of damage), and sometimes evoked potential studies (which measure electrical signals in response to stimuli) or a spinal tap to analyze cerebrospinal fluid.

5. Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

What It Is: Inflammatory Bowel Disease is a broad term that primarily refers to two conditions: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Both are characterized by chronic, destructive inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, but they affect different areas. Ulcerative colitis is limited to the colon (large intestine), while Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus.

Specific Symptoms: The immune attack on the digestive tract leads to symptoms such as persistent diarrhea, severe abdominal pain and cramping, rectal bleeding or bloody stools, unintended weight loss, and profound fatigue. The chronic inflammation can lead to serious complications like bowel obstruction or perforation.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis involves procedures to visualize the GI tract, such as endoscopy (colonoscopy or upper endoscopy), along with imaging studies like CT or MRI. A definitive diagnosis is confirmed by taking tissue samples (biopsies) during endoscopy and examining them for signs of chronic inflammation.

6. Type 1 Diabetes

What It Is: Formerly known as juvenile diabetes, Type 1 Diabetes is an organ-specific autoimmune disease where the immune system seeks out and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Insulin is a crucial hormone that allows your body to use sugar (glucose) from food for energy. Without insulin, sugar builds up in the bloodstream, leading to high blood sugar levels.

Specific Symptoms: The onset of symptoms can be relatively sudden and includes increased thirst and frequent urination, extreme hunger, unintended weight loss, fatigue and weakness, and blurred vision. If untreated, it can lead to a life-threatening condition called diabetic ketoacidosis.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is made through blood tests that measure blood glucose levels. Doctors will also often test for the presence of specific autoantibodies associated with Type 1 Diabetes to confirm the autoimmune cause and distinguish it from the more common Type 2 Diabetes.

7. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

What It Is: Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis is the most common cause of hypothyroidism (an underactive thyroid) in the United States. In this condition, the immune system attacks the thyroid gland, a small, butterfly-shaped gland in the neck. The chronic inflammation gradually impairs the thyroid’s ability to produce the hormones that regulate the body’s metabolism.

Specific Symptoms: The symptoms of an underactive thyroid are often subtle and develop slowly over years. They include persistent fatigue and sluggishness, unexplained weight gain, increased sensitivity to cold, hair loss or thinning, dry skin, constipation, and depression. Some people may develop an enlarged thyroid, known as a goiter.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is confirmed with simple blood tests. Doctors check the level of Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH)—which will be high as the pituitary gland tries to stimulate the failing thyroid—and the levels of thyroid hormones themselves (T4), which will be low. The presence of thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies confirms the autoimmune nature of the condition.

8. Graves’ Disease

What It Is: Graves’ Disease is the functional opposite of Hashimoto’s. It is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism (an overactive thyroid). In this case, the immune system produces an antibody (thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin) that mimics TSH. This antibody constantly stimulates the thyroid gland to overproduce its hormones, sending the body’s metabolism into overdrive.

Specific Symptoms: Symptoms reflect a sped-up metabolism and include anxiety and irritability, a fine tremor in the hands or fingers, unexplained weight loss despite an increased appetite, a rapid or irregular heartbeat (palpitations), and sensitivity to heat. A unique and telling sign of Graves’ Disease is bulging eyes, a condition called Graves’ ophthalmopathy.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis involves blood tests showing low TSH levels (the pituitary gland stops trying to stimulate an already overactive thyroid) and high levels of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4). A test for the specific thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin antibody confirms the diagnosis.

9. Sjögren’s Syndrome

What It Is: Sjögren’s (pronounced “SHOW-grins”) Syndrome is a systemic autoimmune disease that primarily targets the glands responsible for producing moisture in the body, particularly the salivary glands (in the mouth) and lacrimal glands (in the eyes). It can occur on its own (primary Sjögren’s) or alongside another autoimmune disease like RA or Lupus (secondary Sjögren’s).

Specific Symptoms: The hallmark symptoms are severe and persistent dry eyes (which may feel gritty or burning) and a dry mouth (which can make it difficult to swallow or speak). However, as a systemic disease, it can also cause widespread symptoms like debilitating fatigue, chronic pain, and joint inflammation. It can also affect other organs, including the kidneys, lungs, and nerves.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is based on the characteristic symptoms, a physical exam, and blood tests for specific antibodies, namely anti-SSA/Ro and anti-SSB/La. Doctors may also perform tests to measure tear and saliva production, such as the Schirmer test for tear production.

10. Celiac Disease

What It Is: Celiac Disease is a unique autoimmune disease where the ingestion of gluten—a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye—triggers an immune response that attacks and damages the lining of the small intestine. This damage impairs the body’s ability to absorb nutrients from food, leading to malabsorption and a wide range of health problems.

Specific Symptoms: Symptoms can be digestive or manifest elsewhere in the body. Classic digestive symptoms include bloating, chronic diarrhea, constipation, gas, and abdominal pain. However, many adults have non-digestive symptoms, including unexplained iron-deficiency anemia, profound fatigue, bone or joint pain, headaches, and a specific itchy, blistering skin rash called dermatitis herpetiformis.

Diagnosis: The first step is usually a blood test to check for high levels of specific autoantibodies, such as tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA). If the blood test is positive, the diagnosis is typically confirmed with a biopsy of the small intestine, taken during an upper endoscopy, which will show damage to the intestinal villi.

Quick Comparison of Common Autoimmune Diseases

| Disease | Primary Target | Hallmark Symptom | Key Diagnostic Clue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Joint Lining (Synovium) | Symmetrical Morning Stiffness | Anti-CCP Antibodies |

| Multiple Sclerosis | Nerve Sheaths (Myelin) | Numbness, Vision Loss, Fatigue | Lesions on Brain/Spine MRI |

| Celiac Disease | Small Intestine Lining | Digestive Distress After Gluten | tTG-IgA Antibodies |

| Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis | Thyroid Gland | Fatigue, Weight Gain, Cold Intolerance | High TSH, TPO Antibodies |

| Systemic Lupus (SLE) | Multiple Organs (Systemic) | Butterfly Rash, Fatigue, Joint Pain | Positive ANA Test |

| Graves’ Disease | Thyroid Gland (Stimulation) | Weight Loss, Rapid Heartbeat, Anxiety | Low TSH, Thyroid-Stimulating Antibody |

How Are Autoimmune Diseases Diagnosed?

Diagnosing an autoimmune disease can be a long and frustrating journey.

Because symptoms are often vague, overlap between different conditions, and can come and go, it’s not uncommon for patients to see multiple doctors over several years before getting a definitive answer.

There is no single test for most autoimmune diseases; rather, diagnosis is a process of careful investigation and elimination.

The diagnostic process typically follows a structured approach:

- Comprehensive Medical and Family History: The first and most crucial step. Your doctor will ask detailed questions about your specific symptoms, when they started, what makes them better or worse, and whether any family members have been diagnosed with an autoimmune condition. This family history is a vital clue due to the strong genetic link.

- Thorough Physical Exam: Your doctor will perform a head-to-toe physical examination, looking for subtle physical signs of inflammation. This could include checking for joint swelling or tenderness, examining the skin for rashes, listening to the heart and lungs, and feeling the neck for an enlarged thyroid gland.

- Key Blood Tests: Blood tests are essential for detecting signs of immune system activity and inflammation. Common tests include:

- Antinuclear Antibody (ANA): This is often used as an initial screening test. A positive result indicates that your immune system is stimulated and is producing autoantibodies. While a positive ANA is common in many autoimmune diseases like Lupus, it does not confirm a specific diagnosis and can even be positive in healthy individuals. A recent study noted that a positive ANA was predictive of developing an autoimmune disease after COVID-19 infection (PubMed).

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) & C-Reactive Protein (CRP): These are general markers of inflammation somewhere in the body. Elevated levels suggest an active inflammatory process but do not point to a specific cause.

- Specific Autoantibody Tests: If a particular disease is suspected based on symptoms, doctors will order tests for autoantibodies known to be associated with that condition. Examples include anti-CCP for Rheumatoid Arthritis or TPO antibodies for Hashimoto’s.

- Biopsy: In some cases, a definitive diagnosis requires examining a small sample of tissue under a microscope. A biopsy can reveal characteristic patterns of inflammation and damage caused by the immune attack. This is a standard procedure for diagnosing conditions like Celiac Disease (from the small intestine), Psoriasis (from the skin), or Lupus Nephritis (from the kidney).

Gender Disparity in Autoimmune Disease

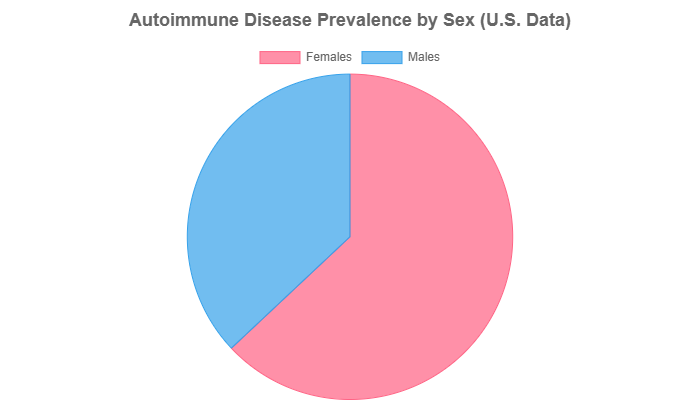

One of the most striking epidemiological features of autoimmune disease is its significant gender bias.

Data consistently shows that women are disproportionately affected. According to the NIH’s Office of Research on Women’s Health, nearly 80% of those with an autoimmune disease are women.

A 2025 study from the Mayo Clinic further quantified this, finding that females accounted for 63% of diagnosed cases compared to 37% for males.

The reasons for this disparity are complex and are thought to involve a combination of hormonal differences (estrogen’s role in immune response), genetic factors (related to the X chromosome), and environmental exposures.

What Are the Latest Treatments for Autoimmune Disease?

The landscape of treatment for autoimmune disease has been revolutionized over the past two decades.

While there is still no cure, the goal of therapy has shifted from simply managing symptoms to actively modifying the disease course, reducing inflammation, suppressing the overactive immune response, and ultimately achieving long-term remission.

Foundational Treatments

These are often the first line of defense to manage symptoms and control acute inflammation.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Over-the-counter drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen can help reduce pain and minor inflammation.

- Corticosteroids: Drugs like prednisone are powerful, broad-spectrum anti-inflammatories that can quickly control severe flares. However, due to significant long-term side effects (e.g., weight gain, bone loss, increased infection risk), they are typically used for short periods.

Targeted Biologics and DMARDs

This class of drugs represents a major leap forward in treating autoimmune disease. Instead of suppressing the entire immune system like corticosteroids, they target specific molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory process.

- Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs): These drugs, like methotrexate, work more slowly than steroids but can alter the underlying disease and prevent long-term damage.

- Biologics: These are a newer, more advanced type of DMARD. They are genetically engineered proteins derived from living cells that target very specific parts of the immune system, such as inflammatory proteins (like TNF-alpha) or specific immune cells (like B-cells). This targeted approach often leads to greater efficacy and fewer side effects than broader immunosuppressants (Molecular Pathogenesis and Targeted Therapy).

The Future is Here: Groundbreaking Cellular Therapies

The most exciting frontier in treatment involves harnessing the power of cellular immunotherapy to “reboot” the immune system.

This approach offers the potential for deep, long-lasting remission, possibly even a functional cure.

The most promising technique for curing autoimmune diseases is **CAR T-cell therapy**. Once used exclusively for treating blood cancers, this therapy is now being studied in clinical trials for severe autoimmune diseases like Lupus, Myositis, and Systemic Sclerosis with encouraging results. – Based on research from Immunotherapy Strategy for Systemic Autoimmune Diseases and clinical trials at University of Chicago Medicine.

The concept is revolutionary: a patient’s own T-cells (a type of immune cell) are removed from their body.

They are then genetically engineered in a lab to express a special receptor—a Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)—that allows them to recognize and target a specific marker on the surface of the faulty B-cells that are producing the autoantibodies.

These re-engineered “super cells” are then infused back into the patient, where they seek out and eliminate the disease-causing B-cells.

This targeted elimination aims to reset the immune system, potentially leading to long-term, drug-free remission.

Frequently Asked Questions About Autoimmune Disease

Can an autoimmune disease be cured?

No, there is currently no definitive cure for any autoimmune disease. However, with modern treatments, many people can effectively manage their symptoms, control the underlying inflammation, achieve long-term remission, and lead full, active lives.

Is autoimmune disease genetic?

Genetics play a significant role, and these conditions often run in families. However, having the predisposing genes does not guarantee you’ll get the disease. In most cases, an environmental factor, such as an infection or toxin exposure, is needed to trigger it.

Can diet help manage an autoimmune disease?

While no specific “autoimmune diet” is a proven cure, many people find that adopting an anti-inflammatory diet—rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats like omega-3s—can help manage symptoms and reduce overall inflammation. It is crucial to work with a doctor or registered dietitian.

Are autoimmune diseases contagious?

No, absolutely not. You cannot catch an autoimmune disease from another person. They are a result of an individual’s own immune system malfunctioning and are not caused by an infectious agent that can be transmitted.

Who is most at risk for autoimmune diseases?

Women are disproportionately affected, making up nearly 80% of all cases (NIH OADR-ORWH). A family history of any autoimmune condition is also a major risk factor, as is having a pre-existing autoimmune disease.

Can you have more than one autoimmune disease?

Yes, it is relatively common for individuals to develop more than one autoimmune condition. This is known as polyautoimmunity. The underlying genetic and immune dysregulation that causes one disease can make a person susceptible to others.

What kind of doctor treats autoimmune diseases?

This depends on the specific disease and the organs it affects. A rheumatologist is a specialist in arthritis and systemic autoimmune diseases and often serves as the primary specialist. You may also see a neurologist (for MS), endocrinologist (for thyroid/diabetes), dermatologist (for psoriasis), or gastroenterologist (for IBD).

What is the difference between autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases?

It’s a subtle but important distinction in immunology. Autoimmune diseases involve a malfunction of the adaptive immune system (the highly specific T-cells and B-cells). Autoinflammatory diseases involve the innate immune system (the body’s more general, first-line defense) and cause systemic inflammation without the presence of autoantibodies.

Conclusion

Living with an autoimmune disease is a journey defined by complexity, uncertainty, and resilience.

We’ve seen that these conditions, which arise from a mysterious betrayal by our own immune systems, are becoming increasingly common worldwide.

They stem from a complex interplay of genetics and environment and can manifest in a bewildering array of symptoms that affect every part of the body.

Most importantly, the landscape of diagnosis and treatment is evolving faster than ever before.

While a diagnosis can be daunting, understanding your condition is the first and most critical step toward empowerment.

The days of one-size-fits-all, broadly suppressive treatments are giving way to a new era of precision medicine.

Advances in targeted biologics and groundbreaking cellular therapies like CAR T-cells are not just managing symptoms—they are fundamentally changing the course of the disease and offering unprecedented hope for long-term remission and improved quality of life.

If you are experiencing persistent, unexplained symptoms discussed in this guide, it is essential to advocate for yourself and speak with a healthcare provider.

Early and accurate diagnosis remains the cornerstone of effective management and preventing long-term damage. The path forward is one of continued research, growing awareness, and personalized care.

Do you have an experience with an autoimmune disease you’d like to share? Leave a comment below to help others in the community. Sharing this article can also help raise crucial awareness for these often-invisible illnesses.