Primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDDs) are a group of over 450 rare, chronic disorders caused by genetic defects that impair the body’s immune system.

This inherent weakness, often called immunodeficiency, leaves individuals highly susceptible to severe, recurrent, and unusual infections.

Affecting an estimated 500,000 people in the United States alone, these conditions can range from mild enough to go unnoticed until adulthood to severe forms discovered shortly after birth.

Understanding this complex spectrum of diseases is the first step toward better diagnosis, management, and quality of life.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of primary immunodeficiency diseases, from their fundamental causes and symptoms to the latest breakthroughs in treatment and research, empowering patients and families with authoritative knowledge.

In This Article

What is Primary Immunodeficiency?

Primary immunodeficiency, often referred to as PIDD or primary immune disorders, describes a state where the immune system’s ability to fight infectious disease is compromised or entirely absent.

Unlike secondary immunodeficiencies, which are acquired (e.g., from HIV, malnutrition, or immunosuppressive drugs), primary immunodeficiencies are innate.

This means individuals are born with the condition due to one or more genetic mutations.

These genetic errors can affect any part of the immune system, including its key soldiers: B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, phagocytes, and the complement system.

When one of these components is missing or dysfunctional, the body loses a critical line of defense.

This leaves it vulnerable to repeated and often severe infections from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other germs that a healthy immune system would typically handle with ease.

According to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), primary immunodeficiency diseases are rare genetic disorders that impair the immune system. Without a functional immune response, people with primary immunodeficiency diseases may be subject to chronic, debilitating infections.

The severity of this weakened immune system varies dramatically. Some forms of PIDD are so mild they may only cause a slight increase in common infections and go undiagnosed for years.

Others, like Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), are medical emergencies that can be fatal within the first year of life if not treated aggressively.

What Causes Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases?

At its core, every case of primary immunodeficiency is genetic.

The immune system is an incredibly complex network of cells, tissues, and organs, all orchestrated by instructions encoded in our DNA.

A single error—a mutation—in a critical gene can disrupt this entire process.

The Genetic Basis of a Weakened Immune System

Researchers have identified over 450 different genes where mutations can lead to a form of primary immunodeficiency disease.

These mutations can be inherited from one or both parents, or they can occur spontaneously (de novo) in the child’s DNA for the first time. The inheritance pattern depends on the specific gene and disorder:

- X-linked Recessive: The mutated gene is on the X chromosome. These disorders, such as Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and SCID-X1, primarily affect males, who have only one X chromosome.

- Autosomal Recessive: An individual must inherit two copies of the mutated gene (one from each parent) to develop the disorder. Parents are typically carriers without symptoms. Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID) can have this inheritance pattern.

- Autosomal Dominant: Only one copy of the mutated gene is needed to cause the disorder. An affected parent has a 50% chance of passing the condition to each child.

These genetic flaws can lead to a variety of problems, such as the inability to produce antibodies, a lack of certain white blood cells, or the production of immune cells that don’t function correctly.

The result is a critical gap in the body’s defenses against pathogens.

The Impact on the Immune System

The specific type of primary immunodeficiency disease is determined by which part of the immune system is affected. For example:

- B-cell (Antibody) Deficiencies: The most common type of PIDD, accounting for over 50% of cases. The body cannot produce enough antibodies (immunoglobulins) to fight off bacteria.

- T-cell Deficiencies: Affects T-cells, which are crucial for coordinating the immune response and fighting off viruses and fungi. These are often more severe.

- Combined Immunodeficiencies (CIDs): Both B-cells and T-cells are affected. SCID is the most severe form of CID.

- Phagocyte Defects: Affects cells like neutrophils that are supposed to “eat” and destroy invading pathogens.

- Complement Deficiencies: Affects the complement system, a group of proteins that helps antibodies and phagocytes clear pathogens.

Understanding the genetic root of a patient’s immunodeficiency is becoming increasingly vital, as it opens the door to more precise diagnoses and targeted therapies, including the revolutionary field of gene therapy.

What Are the Common Symptoms and Warning Signs?

The hallmark of a primary immunodeficiency is a pattern of infections that are more frequent, severe, or unusual than what is typically seen in the general population.

While symptoms vary widely based on the specific disorder, the Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF) has established warning signs to help identify individuals who may need evaluation.

10 Warning Signs of Primary Immunodeficiency

Recognizing these signs is crucial for early diagnosis. An evaluation for PIDD should be considered if a person experiences two or more of these signs:

- Four or more new ear infections within one year.

- Two or more serious sinus infections within one year.

- Two or more months on antibiotics with little effect.

- Two or more cases of pneumonia within one year.

- Failure of an infant to gain weight or grow normally (failure to thrive).

- Recurrent, deep skin or organ abscesses.

- Persistent thrush in the mouth or fungal infection on the skin.

- Need for intravenous antibiotics to clear infections.

- Two or more deep-seated infections including septicemia (blood infection).

- A family history of primary immunodeficiency.

Beyond Infections: Other Manifestations

While infections are the primary symptom, primary immunodeficiency diseases can cause a wide range of other health problems. The chronic immune dysregulation can lead to:

- Autoimmunity: The immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues, leading to conditions like lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or inflammatory bowel disease. This occurs in a significant portion of PIDD patients.

- Increased Cancer Risk: A dysfunctional immune system is less effective at identifying and destroying cancerous cells. People with certain primary immunodeficiency diseases have a higher risk of developing lymphomas and other cancers, sometimes linked to chronic viral infections like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

- Chronic Inflammation: Persistent, low-grade inflammation can lead to swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), an enlarged spleen (splenomegaly), and chronic lung or digestive issues.

- Allergies and Asthma: Dysregulation can also manifest as severe allergies, eczema, or asthma.

The presence of these non-infectious symptoms, especially in combination with recurrent infections, is a strong indicator that an underlying immunodeficiency may be the root cause.

How Are Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders Diagnosed?

Diagnosing a primary immunodeficiency is a multi-step process that begins with suspicion and ends with precise identification, often at the genetic level. It requires careful clinical evaluation by an immunologist.

Step 1: Clinical History and Physical Examination

The journey begins with a thorough review of the patient’s medical and family history.

The doctor will focus on the pattern of infections: their type, frequency, severity, and the response to treatment.

A physical exam may reveal signs like failure to thrive, chronic skin rashes, or an absence of tonsils or lymph nodes.

Step 2: Initial Screening Blood Tests

If PIDD is suspected, initial blood tests are ordered to get a broad picture of the immune system’s health. These typically include:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Differential: This test measures the number and types of white blood cells, including lymphocytes and neutrophils. Abnormally low counts can be a first clue.

- Quantitative Immunoglobulin (Ig) Levels: This measures the levels of the main antibody types in the blood: IgG, IgA, and IgM. Low levels are a hallmark of antibody deficiencies.

Step 3: Advanced Immunological Testing

If screening tests are abnormal or suspicion remains high, more specialized tests are performed to pinpoint the defect:

- Antibody Function Tests: The doctor assesses the immune system’s ability to produce specific antibodies in response to vaccines (e.g., tetanus, pneumococcus). A poor response despite normal Ig levels indicates a functional defect.

- Lymphocyte Subset Enumeration: Using a technique called flow cytometry, this test counts the specific populations of immune cells, such as T-cells (CD4+, CD8+), B-cells, and NK cells.

- Complement System Assays: Tests like CH50 measure the activity of the complement protein cascade.

Step 4: Genetic Testing

The definitive diagnosis for many primary immunodeficiency diseases comes from genetic testing.

By sequencing a patient’s DNA, doctors can identify the specific mutation responsible for the disorder. This is crucial for:

- Confirming the diagnosis with certainty.

- Providing a prognosis based on the known outcomes of that specific mutation.

- Guiding treatment decisions, especially for targeted therapies like gene therapy.

- Enabling genetic counseling for the family to understand inheritance risks.

Recent advances, such as AI-powered diagnostic tools, are showing promise in reducing the diagnostic odyssey for patients, with studies suggesting a potential 60% reduction in the time to diagnosis.

What Are the Main Types of Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases?

The International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS) currently classifies over 450 distinct primary immunodeficiency disorders.

They are generally grouped based on the primary part of the immune system that is affected. The table below summarizes some of the major categories and examples.

| Category of PIDD | Primary Defect | Common Examples | Typical Infections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predominantly Antibody Deficiencies | Poor B-cell function or development; low antibody levels. | Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID), X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA), Selective IgA Deficiency | Recurrent bacterial infections, especially sinus, lung (pneumonia), and ear infections. |

| Combined Immunodeficiencies (CIDs) | Defects in both T-cell and B-cell function. | Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome, Ataxia-Telangiectasia (A-T) | Severe bacterial, viral, and fungal infections; opportunistic infections (e.g., PCP pneumonia). Often life-threatening. |

| Phagocyte Number or Function Defects | Problems with neutrophils and other phagocytes that engulf pathogens. | Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD), Severe Congenital Neutropenia | Deep-seated abscesses in skin, lungs, and liver; infections with unusual bacteria and fungi. |

| Diseases of Immune Dysregulation | Immune system is overactive and poorly controlled, leading to autoimmunity and inflammation. | Immune Dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) Syndrome; Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (ALPS) | Less about infection and more about severe autoimmune symptoms affecting multiple organs. |

| Complement Deficiencies | Absence of one or more proteins in the complement system. | C2 Deficiency, Terminal Complement Component Deficiency | Recurrent infections with specific encapsulated bacteria (e.g., Neisseria meningitidis); increased risk of autoimmune disease like lupus. |

This classification helps clinicians understand the patient’s vulnerabilities and tailor preventative and therapeutic strategies accordingly.

For a detailed list of individual primary immunodeficiency diseases, the NIAID provides an extensive resource on the types it is currently studying.

How Are Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Treated?

Treatment for primary immunodeficiency is highly individualized and aims to prevent infections, manage existing ones, and, where possible, correct the underlying immune defect.

The approach is multi-faceted and has evolved significantly thanks to ongoing research.

Cornerstone Therapy: Immunoglobulin (Ig) Replacement

For patients with antibody deficiencies (the most common form of PIDD), immunoglobulin replacement therapy is a life-saving treatment.

This therapy provides the patient with pooled antibodies from thousands of healthy plasma donors.

- Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG): Administered directly into a vein, typically in a hospital or infusion center, every 3-4 weeks.

- Subcutaneous Immunoglobulin (SCIG): Administered under the skin, usually by the patient or a caregiver at home, on a more frequent basis (e.g., daily or weekly).

Recent studies have focused on personalized dosing, which has been shown to improve quality of life by up to 70% by tailoring infusion schedules and amounts to individual patient needs.

This therapy does not cure the immunodeficiency but effectively replaces the missing function, drastically reducing the rate and severity of infections.

Prophylactic Antibiotics and Antifungals

Many individuals with PIDD take daily low-dose antibiotics or other antimicrobial medications to prevent infections from starting.

This is a crucial preventative measure, especially for those with defects in T-cells or phagocytes who are vulnerable to specific types of pathogens.

Curative Therapies: Stem Cell Transplant and Gene Therapy

For the most severe forms of PIDD, such as SCID, treatments that can potentially cure the disease are available.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

Also known as a bone marrow transplant, HSCT replaces the patient’s defective immune system with a healthy one from a donor. The ideal donor is a genetically matched sibling.

However, advances in transplantation techniques have made it possible to use matched unrelated donors or half-matched (haploidentical) family members with high success rates (over 95% in some cases), especially when performed in early infancy.

Gene Therapy

This cutting-edge approach aims to correct the genetic defect in the patient’s own cells. The process typically involves:

- Harvesting the patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells.

- Using a modified, harmless virus (a vector) or a gene-editing tool like CRISPR to deliver a correct copy of the faulty gene into these cells.

- Infusing the corrected cells back into the patient, where they can grow and produce a functional immune system.

Gene therapy has shown remarkable success for several types of SCID and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and is a major focus of current research for many other primary immunodeficiency diseases.

What Is It Like to Live with a Primary Immunodeficiency?

Living with a chronic, invisible illness like primary immunodeficiency presents a unique set of challenges that extend far beyond the physical symptoms.

It impacts daily routines, mental health, and social interactions.

The Daily Burden of Management

A person with PIDD often juggles a complex regimen of treatments.

This can include weekly or monthly infusions, daily prophylactic medications, and frequent doctor’s appointments.

There is a constant need for vigilance—avoiding sick contacts, practicing meticulous hygiene, and monitoring for the earliest signs of infection.

Simple activities that others take for granted, like attending school, going to the movies, or traveling, require careful planning and risk assessment.

One of the most frequent questions from patients is, “Can I travel with PIDD?” The answer is yes, but it involves coordinating with doctors, packing sufficient medication (often requiring refrigeration), and taking extra precautions.

The Psychological and Social Impact

The constant threat of illness can lead to significant anxiety and stress for both patients and their families.

Children may feel isolated from their peers, while adults may struggle with career limitations and the financial burden of lifelong treatment.

The genetic nature of PIDD also raises difficult questions about family planning, with many patients asking, “Will my children have PIDD?” Genetic counseling is a critical resource for addressing these concerns.

Finding Strength in Community

Despite the challenges, many individuals with PIDD lead full and productive lives.

A key factor is strong support systems. Organizations like the Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF) play a vital role by connecting patients, providing educational resources, and advocating for the community.

Events like the IDF National Conference create a space for shared experience and strength, reminding individuals they are not alone.

“Join us for a transformative experience where every story, voice, and journey creates something extraordinary. A mosaic showcases the beauty of diversity and strength that arises from unique pieces coming together.” – Immune Deficiency Foundation, on their National Conference.

This sense of community helps transform the journey with a weakened immune system from one of isolation to one of shared resilience and empowerment.

What Is the Latest Research on Immunodeficiency?

The field of primary immunodeficiency is one of the most dynamic areas in medicine, with research rapidly translating into life-changing clinical practice.

Recent studies (2022-2024) highlight several emerging trends that are shaping the future of PIDD care.

Key Takeaways from Recent Research

- Newborn Screening for SCID is dramatically improving outcomes, with studies showing an 85% reduction in mortality when diagnosis and treatment occur in the first few months of life.

- Gene Therapy using CRISPR and other advanced vectors is moving into Phase II/III clinical trials, offering the promise of a cure for a growing number of primary immunodeficiency diseases.

- Personalized Medicine, including tailored immunoglobulin dosing and treatments based on a patient’s specific genetic profile, is enhancing quality of life and treatment efficacy.

- The Role of the Microbiome is a new frontier, with research exploring the link between gut bacteria composition (dysbiosis) and disease severity in PIDD patients.

Focus Areas of Recent Scientific Studies

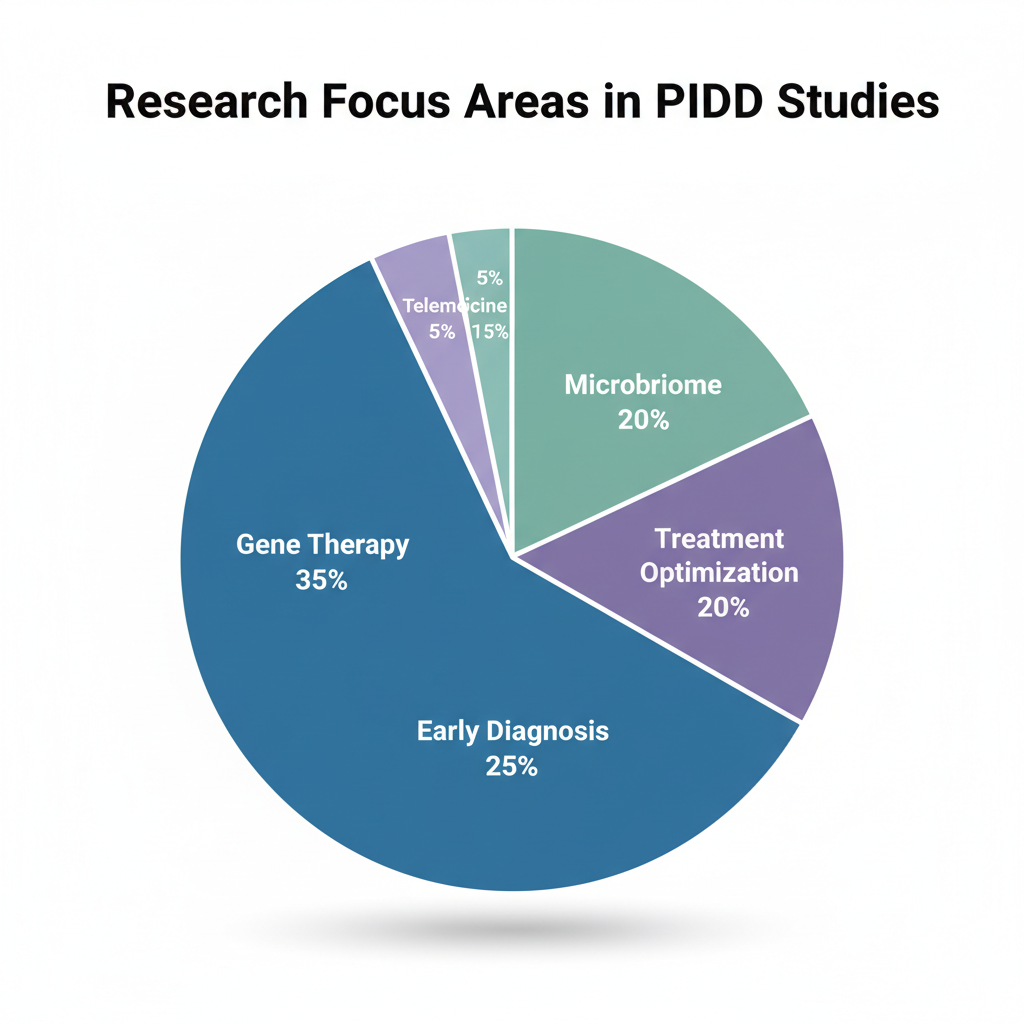

Analysis of recent scientific publications reveals a clear focus on transformative therapies and diagnostics.

Gene therapy and early diagnosis are receiving the most significant attention, reflecting a shift from management to curative and preventative strategies.

Distribution of research focus in recent PIDD studies (2022-2024).

The Rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI is emerging as a powerful tool in the fight against immunodeficiency. Machine learning algorithms are being developed to:

- Accelerate Diagnosis: By analyzing complex patterns in patient data (symptoms, lab results, genetics), AI can help clinicians identify potential PIDD cases much earlier, potentially cutting diagnostic time by up to 60%.

- Predict Complications: AI models can help predict which patients are at higher risk for developing specific complications like autoimmunity or cancer, allowing for proactive monitoring.

- Optimize Treatment: AI can help determine the most effective treatment protocols and dosages for individual patients based on their unique biological markers.

These advancements, supported by institutions like the NIAID’s Primary Immune Deficiency Clinic, are not just academic exercises, they are actively improving diagnostics, creating new treatments, and offering hope for a future where PIDD can be more effectively managed or even cured.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How long does it take to get a primary immunodeficiency diagnosis?

The time to diagnosis varies widely, from days for severe newborn cases to many years for milder adult-onset forms. This “diagnostic odyssey” is a major challenge, but increased awareness and advanced genetic testing are helping to shorten this period significantly.

2. If I have a PIDD, will my children inherit it?

It depends on the specific type of PIDD and its inheritance pattern. Genetic counseling is essential to understand the risk. For some types, the risk is 50% for each child, while for others it is much lower or depends on the partner’s genetics.

3. Is immunoglobulin (Ig) replacement therapy a lifelong treatment?

For most patients with antibody deficiencies, Ig therapy is a lifelong commitment as it replaces a function the body cannot perform. It is a management therapy, not a cure. The only curative options currently are stem cell transplant or gene therapy for specific primary immunodeficiency diseases.

4. What infections are most dangerous for someone with a PIDD?

This depends on the specific immune defect. Those with antibody deficiencies are prone to bacterial pneumonia and sinusitis. T-cell defects increase vulnerability to viruses, fungi, and opportunistic infections like Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP), which can be life-threatening.

5. Can you develop a primary immunodeficiency as an adult?

While the genetic defect is present from birth, some milder forms of PIDD, like Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID), may not cause significant symptoms until adulthood. It is not “developed” as an adult, but rather diagnosed then.

6. What is the difference between primary and secondary immunodeficiency?

Primary immunodeficiency is genetic and present from birth. Secondary (or acquired) immunodeficiency develops later in life due to external factors like HIV infection, chemotherapy, certain medications (e.g., steroids), or severe malnutrition.

7. Can diet and lifestyle improve a primary immunodeficiency?

While a healthy diet, good sleep, and stress management support overall health, they cannot correct the underlying genetic defect of a PIDD. These practices are complementary to, not a replacement for, medical treatment like Ig therapy or prophylactic antibiotics.

8. Is a PIDD considered a disability?

Yes, depending on its severity, a primary immunodeficiency can be considered a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the United States. It can substantially limit major life activities, such as the body’s ability to fight infection.

Conclusion

Primary immunodeficiency diseases represent a complex and challenging group of disorders, but the landscape of care is brighter than ever before.

From a time of diagnostic uncertainty and limited options, we have entered an era of profound scientific progress.

Advances in newborn screening are saving lives, while personalized immunoglobulin therapies are dramatically improving quality of life.

The future, powered by revolutionary treatments like stem cell transplantation and gene therapy, holds the promise of a cure for an increasing number of these conditions.

Research into the microbiome and the application of artificial intelligence are opening new doors to understanding and managing this weakened immune system with unprecedented precision.

If you or a loved one are navigating this journey, know that you are not alone.

A wealth of resources and a vibrant community are available to provide support and guidance.

The key is early diagnosis and proactive management in partnership with an immunology specialist.

Take the next step: If you recognize the warning signs discussed in this guide, speak with your doctor about an evaluation. Share this article with your network to raise awareness and help others find the answers they need.

Medical Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The information contained herein is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.