Shingles, medically known as herpes zoster, is a painful viral infection that causes a blistering rash, typically on one side of the body.

It’s caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus—the same virus that causes chickenpox.

If you’ve ever had chickenpox, the virus remains dormant in your nerve tissue and can reawaken years later as shingles.

This condition is far more common than many realize.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 1 in 3 people in the United States will develop shingles in their lifetime, with nearly one million cases occurring annually.

The risk of developing shingles and its potential complications increases significantly as you get older.

While the shingles rash is its most visible sign, the condition is defined by its often excruciating nerve pain, which can sometimes persist for months or even years after the rash has cleared.

Understanding this condition is the first step toward effective management and prevention.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the complete timeline of shingles symptoms, identify key risk factors, detail modern medical treatments and home care strategies and explain the crucial role of vaccination in preventing this painful illness.

Continue reading to gain a deep understanding of shingles and learn actionable steps to protect yourself and manage this condition effectively.

In This Article

What Exactly Causes Shingles? The Chickenpox Connection

The root cause of shingles lies with a specific and resilient virus: the varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

This virus is a member of the herpesvirus family and is responsible for two distinct, yet related, illnesses that occur at different stages of a person’s life.

The Culprit: Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV)

First, VZV causes varicella, more commonly known as chickenpox.

This primary infection is a highly contagious and well-known childhood disease characterized by an itchy, all-over rash of small blisters.

After a person recovers from chickenpox, the immune system successfully fights off the active infection, but it doesn’t eliminate the virus from the body entirely.

Instead, the varicella-zoster virus retreats into a state of latency.

It travels from the skin along nerve fibers to the sensory ganglia—clusters of nerve cells located near the spinal cord and brainstem, specifically the dorsal root ganglia.

Here, the virus lies “dormant” or “asleep”, silently residing within the nerve cells for decades without causing any symptoms.

The person is not contagious and feels perfectly healthy during this period.

Why Does the Virus Reactivate?

Shingles, or herpes zoster, occurs when this dormant virus reactivates.

The primary trigger for this reawakening is a decline in the body’s cell-mediated immunity to VZV.

This specific arm of the immune system, led by T-cells, is responsible for keeping the latent virus in check.

When this immune surveillance weakens, the virus can begin to replicate again within the nerve ganglion.

From there, it travels back down the nerve fiber to the area of skin supplied by that specific nerve, known as a dermatome.

This is why the shingles rash is characteristically confined to a single, band-like strip on one side of the body—it follows the path of the affected nerve.

Several factors can lead to the decline in immunity that allows shingles to emerge:

- Natural Aging (Immunosenescence): This is the single most significant risk factor. As we age, our immune system naturally becomes less robust. This age-related decline in immune function, known as immunosenescence, makes it harder for the body to suppress the latent VZV, which is why shingles is most common in adults over 50.

- Medical Conditions that Weaken the Immune System: Certain diseases directly compromise the immune system, creating an opportunity for VZV to reactivate. These include:

- HIV/AIDS, which attacks T-cells directly.

- Cancers, particularly blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma.

- Autoimmune diseases such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis.

- Immunosuppressive Medications: Drugs designed to suppress the immune system can also trigger shingles. This includes:

- Chemotherapy and radiation for cancer treatment.

- High-dose corticosteroids like prednisone, used for a variety of inflammatory conditions.

- Drugs taken to prevent organ rejection after a transplant.

- Significant Physical or Emotional Stress: While more difficult to prove with the same scientific certainty as other factors, many patients report that their shingles outbreak was preceded by a period of intense stress, a major surgery, or a significant injury. As noted in a comprehensive review on StatPearls, emotional stress is considered a potential trigger, likely because high levels of stress hormones like cortisol can temporarily suppress immune function.

In essence, you don’t “catch” shingles. It emerges from within when your body’s defenses against a long-held viral resident are lowered.

What Are the Symptoms of Shingles? A Stage-by-Stage Timeline

The experience of shingles unfolds in distinct phases, often beginning with “invisible” symptoms long before the tell-tale rash appears.

Understanding this timeline is critical for early diagnosis and treatment, which can significantly impact the severity and duration of the illness.

Phase 1: The Pre-Eruptive (Prodromal) Stage (1-5 Days Before the Rash)

This initial phase is characterized by sensations in a specific, localized area of skin on one side of the body.

This area corresponds to a single dermatome—the patch of skin supplied by a single spinal nerve.

During this stage, there are no visible signs on the skin, which can make it confusing and difficult to diagnose.

The most common prodromal symptoms include:

- Localized Pain: This is the hallmark of early shingles. The pain can vary widely in character and intensity, described as a constant burning, tingling, itching, stabbing or shooting pain. The skin in the affected area may become extremely sensitive to touch (a condition called allodynia), where even the light pressure of clothing can feel painful.

- Systemic Symptoms: In addition to the localized pain, some people may experience general feelings of being unwell, similar to the onset of the flu. These can include:

- Headache

- Fever and chills

- General fatigue or malaise

- Upset stomach

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

Because there is no rash yet, these symptoms are often mistaken for other conditions, such as a pulled muscle, a heart or lung issue (if on the chest), or even a kidney stone (if on the back or flank).

Phase 2: The Acute Eruptive Stage (The Rash Appears)

This is the phase most people associate with shingles.

The rash develops within the dermatome where the prodromal pain was felt and evolves through several distinct steps:

- Day 1-3: The rash begins as a cluster of red, flat spots (macules) that quickly become raised bumps (papules). A key diagnostic feature is its unilateral (one-sided) and band-like pattern. It almost never crosses the midline of the body. The most common locations are the torso (wrapping around from the back to the chest or abdomen) or one side of the face.

- Day 3-5: The bumps rapidly evolve into fluid-filled blisters, known as vesicles. These vesicles look similar to chickenpox blisters but are typically clustered together in a denser pattern. The fluid inside is initially clear but may become cloudy or purulent over the next few days. The pain during this stage is often at its most intense.

- Day 7-10: The blisters reach their peak, then begin to rupture, ooze fluid, and subsequently dry out. They form yellowish or brownish crusts or scabs. It is during this blistering and oozing phase that the virus can be transmitted to others (causing chickenpox, not shingles). Once all blisters have crusted over, the person is generally no longer considered contagious.

- Weeks 2-4: The scabs gradually fall off over the next one to two weeks. The skin underneath may appear pink, red, or have patches of hyperpigmentation (darker skin) or hypopigmentation (lighter skin), especially in individuals with darker skin tones. This discoloration can take months to fade. Scarring is uncommon unless the rash becomes infected with bacteria (often from scratching) or in very severe cases.

The entire episode, from the first blister to the last scab falling off, typically lasts between two and four weeks in a healthy individual.

However, the pain can persist long after the rash is gone, leading to the most common complication of shingles.

Who Is Most at Risk for Developing Shingles?

While anyone who has had chickenpox can theoretically develop shingles, the risk is not evenly distributed.

A combination of factors related to age, immune health, and even genetics can significantly increase a person’s likelihood of experiencing a VZV reactivation.

Understanding these risk factors is key to prevention.

Primary Risk Factors (The “Big Three”)

- Age: This is the most critical risk factor. The risk of shingles begins to rise around age 50 and increases sharply with each passing decade. According to the National Institute on Aging (NIA), about half of all shingles cases occur in people aged 60 or older. This is due to the natural, age-related decline of the immune system, or immunosenescence.

- Having Had Chickenpox: This is a prerequisite. You cannot get shingles unless your body is already hosting the latent varicella-zoster virus from a prior chickenpox infection. Even if you don’t remember having chickenpox, over 99% of adults born before 1980 in the U.S. have been exposed to the virus.

- A Weakened Immune System (Immunocompromise): Any condition or treatment that suppresses the immune system dramatically increases the risk of shingles. This includes not only the major conditions like HIV/AIDS and cancer but also the use of immunosuppressive drugs for autoimmune diseases or organ transplants.

In-Depth Risk Factors: A Scientific View

Beyond the basics, a large-scale 2020 meta-analysis published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine by Marra et al. synthesized data from 88 studies to provide a more detailed picture of who is at risk.

This research highlights several other significant factors:

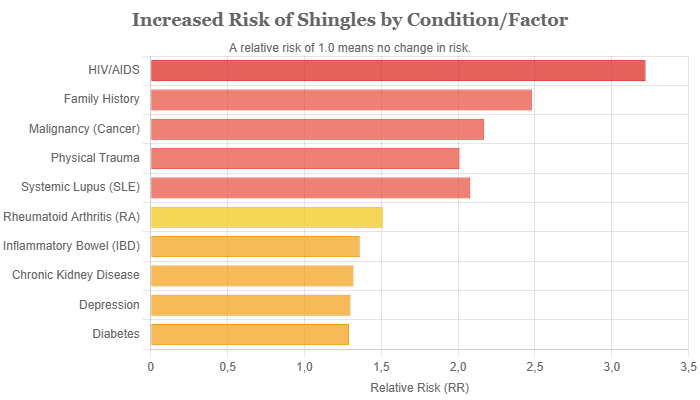

Chart: Relative risk increase for developing shingles based on various health conditions and factors. Data adapted from Marra et al. (2020) meta-analysis. A relative risk of 2.0 means the risk is doubled.

- Specific Comorbidities: The study confirmed that having certain chronic health conditions is an independent risk factor, even without the use of immunosuppressive drugs. The presence of systemic inflammation and immune dysregulation in these diseases likely contributes to the risk. Notable conditions include:

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Increased risk by ~108% (Relative Risk [RR] ≈ 2.08)

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Increased risk by ~51% (RR ≈ 1.51)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Increased risk by ~36% (RR ≈ 1.36)

- Chronic Kidney Disease: Increased risk by ~32% (RR ≈ 1.32)

- Diabetes Mellitus: Increased risk by ~29% (RR ≈ 1.29)

- Depression: Increased risk by ~30% (RR ≈ 1.30)

- Family History: Having a close blood relative (like a parent or sibling) who has had shingles was associated with a significantly higher risk (RR ≈ 2.48). This suggests a possible genetic predisposition, perhaps related to specific genes that control the immune response to VZV.

- Gender and Race: The analysis found consistent, though modest, trends. Females were found to have a slightly higher risk of developing shingles than males (about 19% higher). Conversely, individuals of Black race were found to have a significantly lower risk compared to Caucasians (about 31% lower). The reasons for these differences are not fully understood but may involve a combination of genetic, environmental, and healthcare access factors.

- Physical Trauma: The study also supported the link between physical trauma and shingles reactivation. A significant injury or surgery to a specific area of the body was associated with a doubled risk (RR ≈ 2.01) of developing a shingles rash in that same dermatome, a phenomenon known as “locus minoris resistentiae” (a site of lesser resistance).

This deeper analysis shows that the risk of shingles is not just about age, it’s a complex interplay of immune health, chronic disease, genetics and even physical events.

How is Shingles Diagnosed? When to Call Your Doctor

Accurate and timely diagnosis of shingles is paramount.

The effectiveness of antiviral treatment is highest when initiated early, ideally within 72 hours (3 days) of the rash first appearing.

Prompt treatment can reduce the severity of the pain, shorten the duration of the rash, and significantly lower the risk of developing long-term complications like postherpetic neuralgia.

If you suspect you have shingles, do not wait. Contact your healthcare provider immediately. This is especially critical if the rash is on your face, as it could affect your eyes and lead to serious complications.

Clinical Diagnosis: The Primary Method

In the vast majority of cases, a healthcare provider can diagnose shingles based on a physical examination and a discussion of your symptoms. The diagnosis relies on two key features:

- History of Pain: The patient’s description of a localized, burning, or tingling pain that began a few days before the rash is a classic clue.

- Characteristic Rash: The appearance of a unilateral (one-sided), dermatomal (band-like) rash with blisters is highly indicative of shingles. The provider will look for this distinctive pattern on your torso, face or limbs.

For most healthy individuals with a typical presentation, this clinical diagnosis is sufficient, and no further testing is needed.

When Are Lab Tests Needed?

In some situations, the diagnosis may not be clear-cut, and laboratory testing can be used to confirm the presence of the varicella-zoster virus. These situations include:

- Atypical Presentation: The rash may not follow a classic dermatome, or it might be more widespread, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

- No Rash (Zoster Sine Herpete): In rare cases, a person can experience the characteristic nerve pain of shingles without ever developing a rash. This makes diagnosis very difficult and often requires testing to rule out other causes of pain.

- Immunocompromised Patients: In these patients, shingles can be more severe and present unusually, making a definitive diagnosis crucial for appropriate management.

- Suspected Ocular Involvement: If the rash is near the eye, testing can confirm VZV as the cause.

The most common and reliable tests for shingles are:

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) Test: This is the gold standard and the test most recommended by the CDC. A healthcare provider will gently unroof a fresh blister and swab the fluid. The PCR test then amplifies and detects the specific DNA of the varicella-zoster virus. It is highly sensitive and specific, providing a definitive result.

- Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) Staining: Similar to PCR, a sample is taken from a blister. The sample is then treated with antibodies tagged with a fluorescent dye that will bind specifically to VZV proteins, which can be seen under a special microscope. It is faster than culture but less sensitive than PCR.

- Tzanck Smear: This is a more historical method that is now rarely used due to its lower sensitivity and specificity. It involves scraping the base of a blister, smearing it on a slide, and looking for characteristic “multinucleated giant cells” under a microscope. While these cells are seen in herpesvirus infections, this test cannot distinguish between VZV and herpes simplex virus (HSV).

Differential Diagnosis: What Else Could It Be?

Part of a thorough diagnosis involves considering other conditions that can mimic the symptoms of shingles, especially in the early stages or in atypical cases. A healthcare provider will work to rule out:

- Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV): HSV, the virus that causes cold sores and genital herpes, can sometimes cause a rash in a dermatome-like pattern (zosteriform herpes simplex), which can be visually indistinguishable from shingles. PCR testing is the best way to differentiate them.

- Contact Dermatitis: An allergic reaction to something that touched the skin, like poison ivy, poison oak, or certain chemicals, can cause a linear, blistering rash. However, it is usually intensely itchy rather than primarily painful.

- Insect Bites: A series of bites from insects like spiders or bedbugs can sometimes appear in a line, but they typically lack the underlying nerve pain of shingles.

- Impetigo: A common bacterial skin infection that causes crusty sores. It is more common in children and usually doesn’t follow a dermatome.

What Are the Treatments for Shingles? (Medical & Home Care)

The management of shingles focuses on two primary goals: fighting the virus to speed up healing and managing the often-severe pain.

Treatment involves a combination of prescription medications and supportive at-home care.

Medical Treatments (Prescription Required)

Starting these medications within 72 hours of the rash onset is crucial for the best outcomes.

Antiviral Medications

This is the cornerstone of shingles treatment.

Antiviral drugs work by inhibiting the replication of the varicella-zoster virus, which helps to shorten the duration of the rash, reduce the severity of symptoms, and lower the risk of complications like PHN.

The three most commonly prescribed oral antivirals are:

| Drug Name (Brand Name) | Standard Dosage | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Valacyclovir (Valtrex) | 1 gram, 3 times a day for 7 days | Excellent absorption into the body and requires fewer doses per day, making it a common first choice. |

| Famciclovir (Famvir) | 500 mg, 3 times a day for 7 days | Also well-absorbed and effective with convenient dosing. |

| Acyclovir (Zovirax) | 800 mg, 5 times a day for 7 days | The oldest of the three drugs. It is effective but has lower bioavailability, requiring more frequent dosing throughout the day. |

Pain Management Medications

Because shingles pain originates from inflamed nerves, standard over-the-counter pain relievers may not be sufficient.

A doctor may prescribe stronger or more targeted medications:

- Nerve Pain Medications (Anticonvulsants): Drugs like Gabapentin (Neurontin) and Pregabalin (Lyrica) are very effective for neuropathic pain. They work by calming overactive nerve signals.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants: In low doses, certain antidepressants like Amitriptyline can help manage nerve pain by altering brain chemicals that are involved in pain perception.

- Corticosteroids: A short course of a steroid like prednisone may be prescribed alongside an antiviral for some patients. It can help reduce inflammation and pain, but its use is debated and typically reserved for moderate to severe cases, as its benefit in preventing PHN is not definitively proven.

- Prescription Pain Relievers: In cases of extreme acute pain, a short course of opioid medication may be necessary, but this is carefully managed by the physician due to the risk of dependence.

At-Home and Over-the-Counter Relief

Supportive care at home is essential for managing discomfort and promoting healing.

These strategies can be used alongside medical treatments:

For Pain & Itching:

- Cool Compresses: Apply a clean, cool, moist washcloth to the blisters for 15-20 minutes several times a day. This can soothe the skin and reduce pain. Avoid using ice packs directly on the skin.

- Soothing Baths: Taking a cool or lukewarm colloidal oatmeal bath can provide significant relief from itching. Avoid hot water, which can worsen irritation.

- Calamine Lotion: After bathing and gently patting the skin dry, applying calamine lotion can help dry out the blisters and soothe the skin.

- OTC Pain Relievers: For mild to moderate pain, over-the-counter options like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) or acetaminophen (Tylenol) can be helpful. Always consult with your doctor before taking any new medication, especially if you have other health conditions or are taking other drugs.

Practical Tips for Comfort and Healing:

- Wear Loose-Fitting Clothing: Choose soft, loose clothing made from natural fibers like cotton or linen. This minimizes friction and pressure on the sensitive rash.

- Keep the Rash Clean and Dry: To prevent a secondary bacterial infection, gently wash the area with mild soap and water daily. Pat it dry carefully with a clean towel (do not rub) or let it air dry.

- Cover the Rash: If you need to be around others, cover the rash with a non-stick (Telfa) sterile dressing. This not only protects the sensitive skin but also prevents the spread of the virus to non-immune individuals.

- Get Plenty of Rest: Your body is fighting a viral infection. Adequate rest and a nutritious diet can support your immune system and aid in recovery.

- Use Distraction Techniques: Managing chronic pain is both a physical and mental challenge. Engaging in hobbies, listening to music, practicing mindfulness or talking with friends can help take your mind off the discomfort.

What Are the Complications of Shingles?

While most people recover from shingles within a few weeks, a significant minority can experience serious and long-lasting complications.

These are more common in older adults and individuals with weakened immune systems.

Early and effective treatment of the initial shingles outbreak is the best way to reduce the risk of these issues.

Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN): The Pain That Lingers

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is by far the most common complication of shingles, affecting an estimated 10-18% of all patients.

The risk increases dramatically with age, with some studies suggesting up to 30% of patients over 80 will develop it.

- Definition: PHN is defined as significant nerve pain that persists for more than 90 days (3 months) after the onset of the shingles rash. It occurs because the reactivated virus can cause permanent damage to the nerve fibers, causing them to send chaotic and exaggerated pain signals to the brain.

- Symptoms: The pain of PHN can be debilitating and can last for months, years, or in some tragic cases, for the rest of a person’s life. It is often described as:

- A deep, constant burning, throbbing or aching pain.

- Intermittent, sharp, jabbing or “electric shock”-like pain.

- Allodynia: Extreme sensitivity to touch, where even the sensation of clothing or a gentle breeze can cause severe pain.

- Pruritus: Persistent, intense itching in the affected area.

- Risk Factors for PHN: The primary risk factors for developing PHN are older age, having severe pain during the acute phase of shingles, having a severe rash and having shingles on the face or torso.

- Treatment for PHN: Managing PHN is challenging and often requires a multi-modal approach. Treatments include topical therapies like lidocaine patches or capsaicin cream, oral medications such as anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin), and certain antidepressants.

Other Serious Complications

While less common than PHN, other complications of shingles can be severe and require immediate medical attention.

- Ophthalmic Shingles (Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus): This is considered a medical emergency. It occurs when shingles affects the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, which supplies the forehead, eyelid, and eye. It can cause severe eye pain, inflammation (keratitis, uveitis), and if not treated aggressively, can lead to permanent corneal scarring, glaucoma and vision loss. A key warning sign is the “Hutchinson’s sign”—the presence of a shingles blister on the tip or side of the nose, which indicates a high likelihood of eye involvement.

- Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (Herpes Zoster Oticus): This occurs when shingles affects the facial nerve near one of your ears. In addition to the painful rash, Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis (drooping on one side of the face), hearing loss, severe vertigo (dizziness), and tinnitus (ringing in the ear). Prompt treatment is essential to improve the chances of a full recovery.

- Neurological Issues: In rare cases, the virus can spread to the central nervous system, leading to life-threatening conditions such as:

- Encephalitis: Inflammation of the brain.

- Meningitis: Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

- Myelitis: Inflammation of the spinal cord, which can cause weakness or paralysis.

- Bacterial Skin Infections: The open blisters of a shingles rash can become infected with bacteria (like Staphylococcus or Streptococcus) if they are not kept clean or are excessively scratched. This can lead to cellulitis, increased pain, and a higher risk of scarring.

- Visceral Dissemination: In severely immunocompromised individuals, the virus can spread throughout the body and infect internal organs like the lungs (pneumonia) or liver (hepatitis). This is a very serious and potentially fatal complication.

Is Shingles Contagious? Separating Fact from Fiction

This is one of the most frequently asked questions about shingles and the answer is nuanced.

It’s crucial to understand the distinction between spreading shingles and spreading the underlying virus.

The Short Answer: No

You cannot “catch” shingles from someone who has it.

Shingles is not a communicable disease in the way that the flu or a cold is.

It is caused by the reactivation of a virus that is already dormant inside a person’s own body.

The Nuanced Explanation: But You Can Catch Chickenpox

While you can’t get shingles from someone else, you can catch chickenpox from a person with an active shingles rash if you are not immune to the virus.

This means you are at risk if you have never had chickenpox and have never received the chickenpox vaccine.

- How it Spreads: The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is present in the fluid of the shingles blisters. The virus is spread through direct contact with the fluid from these open, oozing blisters. It is not spread through coughing, sneezing or casual contact if the rash is covered.

- When is it Contagious? A person with shingles is only contagious during the acute eruptive phase, specifically when the blisters are present and have not yet fully crusted over. They are not contagious before the blisters appear or after all blisters have formed dry scabs.

- Who is at Risk? The primary risk is to individuals who have no immunity to VZV. This includes:

- Infants who are too young to be vaccinated.

- Pregnant women who have never had chickenpox.

- Severely immunocompromised individuals (e.g., transplant recipients, those on chemotherapy).

- Anyone who has never had chickenpox or the vaccine.

How to Prevent Spreading the Virus

If you have shingles, you can take simple but effective steps to prevent transmitting VZV to vulnerable individuals:

- Keep the rash covered at all times. Use a clean, dry, non-stick dressing to cover all the blisters until they have completely crusted over. This is the single most important step.

- Wash your hands frequently. Use soap and water or an alcohol-based hand sanitizer, especially after touching the rash or changing the dressing.

- Avoid touching or scratching the rash. This can lead to bacterial infection and increase the risk of spreading the virus.

- Avoid contact with high-risk individuals until your rash has fully scabbed over. This includes pregnant women, premature infants and anyone with a weakened immune system.

Can Shingles Be Prevented? The Shingrix Vaccine

Yes, for most adults, shingles is a preventable disease.

The primary and most effective method of prevention is vaccination.

The development of a modern, highly effective vaccine has been a major breakthrough in public health.

The Primary Prevention Method: Vaccination with Shingrix

The vaccine currently recommended in the United States is Shingrix (Recombinant Zoster Vaccine or RZV).

It was approved by the FDA in 2017 and has since become the standard of care for shingles prevention.

It’s important to note that an older shingles vaccine, Zostavax (a live zoster vaccine), is no longer available for use in the U.S. as of November 2020.

Shingrix is significantly more effective and is a non-live vaccine, making it safe for a wider range of people.

How Effective is Shingrix?

Shingrix has demonstrated outstanding efficacy in clinical trials and real-world studies. According to the CDC:

- In adults 50 to 69 years old, Shingrix was 97% effective in preventing shingles.

- In adults 70 years and older, it was 91% effective.

- Crucially, it is also highly effective at preventing the most feared complication, postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), reducing the risk by approximately 91% in adults 50 and older.

Protection remains strong, staying above 85% for at least the first seven years after vaccination, with ongoing studies to determine the full duration of immunity.

Who Should Get the Shingrix Vaccine?

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has clear recommendations for Shingrix:

- All healthy adults 50 years and older should get two doses of Shingrix.

- Adults 19 years and older who are or will be immunodeficient or immunosuppressed due to disease or therapy should also get two doses of Shingrix, as they are at higher risk for shingles and its complications.

The recommendation applies even if you:

- Have had shingles in the past. Vaccination can help prevent a recurrence.

- Previously received the Zostavax vaccine. Shingrix provides superior and longer-lasting protection.

- Are not sure if you’ve had chickenpox. Studies show that more than 99% of adults over 40 have had chickenpox, even if they don’t remember it. The vaccine is recommended regardless of your memory of having had chickenpox.

Vaccine Schedule and Common Side Effects

Shingrix is administered as a two-dose series into the muscle of the upper arm:

- The second dose should be given 2 to 6 months after the first dose.

- It is very important to get both doses to ensure long-lasting protection.

Like many vaccines, Shingrix can cause temporary side effects.

These are a normal sign that your immune system is learning to recognize and fight the virus.

Most side effects are mild to moderate and resolve within 2-3 days. Common side effects include:

- Pain, redness and swelling at the injection site.

- Muscle pain (myalgia).

- Fatigue.

- Headache.

- Shivering, fever and stomach upset.

Many people plan for a day or two of rest after their vaccination.

The temporary discomfort from the vaccine is a small price to pay to avoid the potentially debilitating and long-lasting pain of shingles and PHN.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Shingles

1. How long does a shingles attack last?

A typical shingles episode, from the first symptom to the rash fully healing, lasts about 2 to 4 weeks. However, the associated nerve pain can sometimes persist for months or even years, a condition known as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

2. Can you get shingles more than once?

Yes, although it’s not common, it is possible to have more than one episode of shingles. Recurrence is more likely in individuals with weakened immune systems. Vaccination with Shingrix after a shingles episode can significantly reduce the risk of another attack.

3. Can stress cause shingles?

While a weakened immune system is the direct cause, severe emotional or physical stress is widely considered a potential trigger for VZV reactivation. High levels of stress hormones can temporarily suppress immune function, creating an opportunity for the dormant virus to reawaken.

4. What does a mild case of shingles look like?

A mild case of shingles might involve less pain and a smaller, less extensive rash. Some people may only have a few blisters and experience more of an itch or tingling than severe pain. However, even mild cases should be evaluated by a doctor.

5. Do I need the shingles vaccine if I never had chickenpox?

If you have truly never had chickenpox (confirmed by a blood test), you cannot get shingles. However, over 99% of adults born before 1980 have been exposed to the virus, even without a clear memory of the illness. The CDC recommends vaccination for adults 50+ regardless.

6. Can shingles cross the midline of the body?

It is extremely rare for a shingles rash to cross the body’s midline. The virus reactivates in a single nerve ganglion, which supplies a dermatome on either the left or right side. A rash on both sides would suggest a different diagnosis or a severe, disseminated case in an immunocompromised person.

7. What is the fastest way to get rid of shingles?

The fastest way to shorten a shingles attack and reduce its severity is to start antiviral medication (like valacyclovir) as soon as possible, ideally within 72 hours of the rash appearing. There is no “instant cure”, the body must fight off the virus.

8. Is it safe to be around someone with shingles?

Yes, it is generally safe as long as you are immune to chickenpox (from a past infection or vaccine) and you avoid direct contact with the fluid from open blisters. If the person with shingles keeps their rash completely covered, the risk of transmission is extremely low.

9. Does shingles leave scars?

In most cases, shingles does not leave permanent scars. However, scarring can occur if the blisters become infected with bacteria (often from scratching) or in very severe cases. Some people may have temporary or permanent changes in skin pigmentation after the rash heals.

10. Can you have shingles without a rash?

Yes, this rare condition is called zoster sine herpete (shingles without the eruption). Patients experience the characteristic dermatomal nerve pain but never develop a rash. It is very difficult to diagnose and is usually confirmed through blood tests or other laboratory diagnostics.

Conclusion

Shingles is more than just a skin rash, it is a painful and potentially debilitating condition rooted in the reactivation of the chickenpox virus that many of us carry.

We’ve seen that its journey begins with nerve pain, erupts into a characteristic one-sided rash, and carries the risk of serious complications, most notably the persistent nerve pain of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

The key takeaways from this guide are clear and actionable. First, early diagnosis and treatment are vital.

Recognizing the initial symptoms and seeking medical care within the first 72 hours can dramatically alter the course of the illness for the better.

Second, while shingles can be a formidable foe, we are not defenseless.

A combination of antiviral medications, targeted pain management, and supportive home care can effectively manage the acute phase.

Most importantly, for the vast majority of adults, shingles is a preventable disease.

The Shingrix vaccine is a safe and highly effective tool, proven to reduce the risk of both shingles and its most feared complication, PHN, by over 90%.

It represents one of the most significant advancements in adult preventative medicine in recent years.

If you are 50 or older, or if you are over 19 with a weakened immune system, talk to your healthcare provider today about getting the Shingrix vaccine. If you suspect you have active shingles, seek medical attention immediately.

By understanding the enemy, recognizing the risks, and embracing prevention, you can take control of your health and protect yourself from the painful grip of shingles.

We hope this guide has been informative and empowering. Share your experience or questions in the comments below to help others in our community navigate this condition.

Reference

[1] What Causes Shingles to Activate?

https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-causes-shingles-to-activate-5224805

[2] https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/shingles/symptoms-causes/syc-20353054

[3] Prevalence of Shingles Immunization Among Adults Aged …

https://www-doh.nj.gov/doh-shad/indicator/view/ImmShingles.Year.html

[4] Shingles Symptoms and Complications

https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/signs-symptoms/index.html

[5] Risk Factors for Herpes Zoster Infection: A Meta-Analysis

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6984676

[6] Herpes Zoster – StatPearls

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824

[7] Shingles Facts and Statistics: What You Need to Know

https://www.verywellhealth.com/facts-about-shingles-5524786

[8] First Blush: Early Symptoms of Shingles

https://www.healthline.com/health/early-symptoms-shingles

[9] Shingles (Herpes Zoster): Causes, Symptoms & Treatment

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/11036-shingles