Is leaky gut syndrome a real medical condition or a wellness buzzword?

The term has exploded in popularity, often blamed for everything from bloating and fatigue to autoimmune diseases and depression.

Yet, many conventional doctors do not recognize it as a formal diagnosis, creating a confusing landscape for those seeking answers to their chronic health issues.

This article cuts through the noise.

We will explore the robust science behind the concept of increased intestinal permeability—the medical term often used interchangeably with leaky gut.

We’ll separate fact from fiction, examine the evidence linking it to various diseases, and provide actionable, science-backed strategies to support and heal your gut barrier.

While an estimated 60-70 million Americans suffer from digestive diseases, understanding the integrity of our gut lining is more critical than ever.

In This Article

What is Leaky Gut Syndrome, Really?

To understand the controversy, we must first distinguish between the popular term “leaky gut syndrome” and the scientific phenomenon it describes.

While the “syndrome” lacks a formal medical definition, the underlying biological mechanism—a compromised gut barrier—is a well-documented area of medical research.

From Medical Mystery to Scientific Concept: Increased Intestinal Permeability

At its core, what people call Leaky Gut Syndrome is known in scientific literature as increased intestinal permeability or intestinal hyperpermeability.

Your intestinal lining is a vast, dynamic surface covering over 4.000 square feet.

It’s designed to be selectively permeable, acting as a sophisticated gatekeeper.

It allows essential nutrients, water, and electrolytes to pass into your bloodstream while blocking harmful substances like toxins, undigested food particles, and pathogenic bacteria.

Increased intestinal permeability occurs when this gatekeeping system breaks down.

The “gates” become wider or “leakier”, allowing substances that should remain confined to the gut to enter the bloodstream.

This breach can trigger an immune response, leading to systemic inflammation, which researchers now believe is a contributing factor to a wide range of chronic diseases.

As Harvard Health Publishing notes, this concept revives an ancient idea that many illnesses may originate in the gut.

The Anatomy of Your Gut Barrier: More Than Just a Wall

The intestinal barrier is not a simple, single layer of cells. It’s a complex, multi-layered defense system. Key components include:

- The Mucus Layer: A thick, gel-like substance that traps pathogens and prevents them from directly contacting the epithelial cells.

- Epithelial Cells: A single layer of specialized cells (enterocytes) that form the primary physical barrier. They are responsible for nutrient absorption.

- Intercellular Junctions: Protein complexes that stitch epithelial cells together, regulating the passage of substances between them.

- The Gut Microbiota: Trillions of beneficial bacteria that help maintain barrier function, digest food, and compete with harmful microbes.

- The Immune System: A vast network of immune cells (Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue or GALT) lies just beneath the epithelial layer, ready to neutralize any threats that breach the wall.

A “leaky gut” signifies a breakdown in one or more of these defensive layers, most notably the intercellular junctions.

The Role of Tight Junctions and Zonulin

The spaces between your intestinal cells are sealed by structures called tight junctions.

Think of them as the mortar between the bricks of a wall.

These junctions are dynamic, capable of opening and closing to allow small molecules to pass through in a controlled process known as paracellular transport.

A key protein that regulates the opening and closing of these tight junctions is called zonulin.

Research published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences identified zonulin as the only known physiological modulator of tight junctions.

When zonulin levels rise in response to certain triggers (like specific bacteria or gluten in susceptible individuals), it signals the tight junctions to open up.

While this is a normal process, chronic overproduction of zonulin can lead to persistently “leaky” junctions, contributing to increased intestinal permeability.

Is Leaky Gut a Diagnosable Medical Condition?

This is where much of the confusion lies.

If you tell your doctor you have “leaky gut syndrome”, you may be met with skepticism.

This is because it is not a recognized medical diagnosis in the way that, for example, Crohn’s disease is. However, this doesn’t mean your symptoms aren’t real or that intestinal permeability isn’t a valid concern.

The “Syndrome” vs. The “Symptom”: Why Your Doctor Might Be Skeptical

Most of the medical community views increased intestinal permeability as a symptom or a mechanism of disease rather than a standalone disease or “syndrome”.

As the Cleveland Clinic explains, it’s a known feature of conditions like celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

The debate centers on whether a leaky gut can *cause* disease in an otherwise healthy person, or if it is merely a *consequence* of an existing disease process.

“From an MD’s standpoint, it’s a very gray area… ‘Leaky gut’ really means you’ve got a diagnosis that still needs to be made”. – Dr. Donald Kirby, Gastroenterologist, Cleveland Clinic.

The term “syndrome” implies a specific cluster of signs and symptoms with a defined cause.

Because the symptoms attributed to leaky gut are so broad and nonspecific (e.g., fatigue, bloating, joint pain), and can be caused by numerous other conditions, it doesn’t fit the criteria for a formal syndrome.

Debunking Common Diagnostic Myths

The internet is rife with companies offering tests that claim to diagnose leaky gut syndrome.

It’s crucial to approach these with caution.

A 2024 review in The American Journal of Gastroenterology systematically debunks several of these myths:

- Myth 1: Blood tests can diagnose leaky gut. Commercial blood tests for zonulin or antibodies to food proteins are often marketed for this purpose. However, researchers state that current commercial zonulin assays are methodologically flawed and do not reliably correlate with disease states.

- Myth 2: Stool tests can diagnose leaky gut. Some direct-to-consumer tests analyze stool for markers like fecal zonulin, candida, or bacterial imbalances. These tests are largely unregulated, and there is no scientific evidence to support their use for diagnosing intestinal permeability.

- Myth 3: Symptoms alone are enough for a diagnosis. The symptoms associated with leaky gut—bloating, gas, fatigue, brain fog—are incredibly common and overlap with dozens of other conditions, from IBS to thyroid disorders. They are not specific enough to confirm a diagnosis.

How Scientists Actually Measure Intestinal Permeability

While commercial tests are unreliable, scientists do have methods to measure intestinal permeability in a research setting.

These are generally not used for routine clinical diagnosis due to cost, complexity, and lack of standardized protocols.

- Lactulose/Mannitol Test: This is considered a gold standard in research. A person drinks a solution containing two non-digestible sugars: mannitol (a small molecule, easily absorbed) and lactulose (a larger molecule, poorly absorbed). The ratio of these sugars recovered in the urine over several hours can indicate how “leaky” the gut is. A high ratio of lactulose to mannitol suggests increased permeability.

- Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy (CLE): A highly advanced and invasive technique where a tiny microscope is passed through an endoscope to visualize the intestinal lining at a cellular level in real-time. It can directly observe gaps between cells and the leakage of fluorescent dyes.

These tools are helping scientists understand the role of intestinal permeability in disease, but they are not yet practical for everyday clinical use.

What are the Purported Symptoms of Leaky Gut?

Proponents of leaky gut syndrome link it to a vast array of symptoms, affecting nearly every system in the body.

While the scientific backing for many of these claims is weak, the symptoms themselves are very real for those who experience them.

Digestive Distress: The Usual Suspects

The most commonly reported symptoms are gastrointestinal in nature, which is logical given the gut is the primary site of the problem. These include:

- Chronic bloating and gas

- Abdominal pain or cramping

- Diarrhea, constipation, or an alternating pattern (similar to IBS)

- Food sensitivities or intolerances

These symptoms arise from poor digestion, gut inflammation, and an imbalanced microbiome (dysbiosis), all of which are closely intertwined with increased intestinal permeability.

Beyond the Gut: Systemic Symptoms

The theory behind leaky gut is that the leakage of toxins and antigens into the bloodstream triggers body-wide inflammation.

This systemic inflammation is then blamed for a host of extra-intestinal symptoms:

- Neurological: Brain fog, memory problems, anxiety, depression, and headaches.

- Dermatological: Acne, eczema, psoriasis, and rosacea.

- Musculoskeletal: Joint pain, muscle aches, and fibromyalgia.

- General: Chronic fatigue, nutritional deficiencies, and a weakened immune system.

The Critical Link: Correlation vs. Causation

It’s vital to understand the difference between correlation and causation.

Many studies show that people with conditions like chronic fatigue syndrome or autoimmune diseases also have increased intestinal permeability.

This is a correlation. However, it does not prove that the Leaky Gut Syndrome caused the disease.

It’s equally possible that the disease process itself (e.g., chronic inflammation) caused the gut to become leaky.

This “chicken or egg” debate is at the heart of the scientific controversy.

What Truly Causes Increased Intestinal Permeability?

Research has identified several key factors that can disrupt the delicate balance of the gut barrier and contribute to increased permeability.

It’s rarely a single cause, but rather a combination of genetic predisposition, diet, and lifestyle factors.

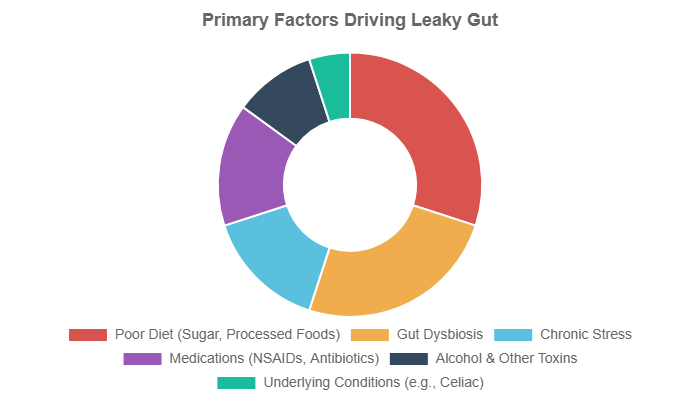

Illustrative chart: Key contributing factors to increased intestinal permeability, based on emphasis in scientific literature.

- Gut Dysbiosis: An imbalance between beneficial and harmful bacteria in the gut is a primary driver. Pathogenic bacteria can produce toxins that degrade the mucus layer and damage epithelial cells.

- Poor Diet: The Standard American Diet (SAD), high in processed foods, sugar (especially fructose), and unhealthy fats, and low in fiber, is strongly implicated. As a 2024 study in Nutrients highlights, a poor diet can directly induce dysbiosis and disrupt barrier integrity.

- Chronic Stress: Psychological stress triggers the release of hormones like cortisol, which can increase gut permeability and alter the microbiome. This is a key component of the gut-brain axis.

- Medications: Long-term use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen and aspirin is a well-known cause of gut lining damage and increased permeability. Antibiotics, while sometimes necessary, can also disrupt the microbiome.

- Excessive Alcohol Consumption: Alcohol can directly damage epithelial cells and contribute to dysbiosis.

- Gluten (in susceptible individuals): For people with celiac disease, gluten triggers a severe autoimmune reaction that damages the gut lining. In those with non-celiac gluten sensitivity, gluten may increase zonulin levels and permeability, though this is still being researched.

- Infections: Acute gastrointestinal infections (food poisoning) can cause temporary or even long-lasting damage to the gut barrier, sometimes leading to post-infectious IBS.

The Scientific Evidence: Which Diseases Are Linked to Leaky Gut?

While leaky gut may not be the root of all modern disease as some claim, robust scientific evidence does link increased intestinal permeability to several specific conditions, particularly autoimmune diseases.

Strong Association: Celiac Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

The link here is undeniable. In celiac disease, gluten ingestion directly leads to severe inflammation and a dramatic increase in intestinal permeability.

In IBD (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), chronic inflammation erodes the gut barrier.

In both cases, increased permeability is a core feature of the disease pathophysiology.

Studies have even found that healthy relatives of Crohn’s patients often have higher-than-normal permeability, suggesting it could be a predisposing factor.

Growing Evidence: Autoimmune Conditions

The “leaky gut” theory of autoimmunity suggests that the passage of antigens from the gut into the bloodstream can trigger an immune response that mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues.

There is growing evidence for this mechanism in several conditions:

- Type 1 Diabetes: Studies have found that increased intestinal permeability often precedes the onset of Type 1 diabetes in genetically susceptible individuals.

- Lupus and Multiple Sclerosis (MS): Research has shown a correlation between these autoimmune diseases and a compromised gut barrier.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: Some studies suggest that changes in gut bacteria and permeability may play a role in triggering the joint inflammation seen in RA.

Emerging Research: IBS and Food Allergies

The connection to Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a hot area of research.

A subset of IBS patients, particularly those with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), have been shown to have increased intestinal permeability.

This may explain the low-grade inflammation and visceral hypersensitivity (a highly sensitive gut) common in the condition.

In food allergies, a leaky gut may allow undigested food proteins to cross the barrier and sensitize the immune system, leading to an allergic reaction.

Restoring barrier function is now being explored as a potential therapeutic strategy.

How Can You Heal and Support Your Gut Barrier? A Practical Guide

While there is no magic pill to “cure” a leaky gut, a comprehensive approach focusing on diet and lifestyle can significantly improve gut barrier function, reduce inflammation, and alleviate symptoms.

The goal is to remove triggers and provide the building blocks your body needs to repair itself.

Foundational Step: The Anti-Inflammatory, Gut-Supportive Diet

Diet is the cornerstone of gut healing.

The focus should be on whole, unprocessed foods that quell inflammation and nourish the gut microbiome. This involves:

- Removing Inflammatory Triggers: This includes processed foods, refined sugars, excessive alcohol, and industrial seed oils. Some individuals may also benefit from a temporary elimination of common irritants like gluten and dairy to see if symptoms improve.

- Increasing Fiber Intake: Soluble and insoluble fiber from a wide variety of plants feeds beneficial gut bacteria, which in turn produce Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) like butyrate. Butyrate is the primary fuel source for your colon cells and helps strengthen the gut barrier.

- Eating the Rainbow: Colorful fruits and vegetables are rich in polyphenols, powerful antioxidants that reduce inflammation and support a healthy microbiome.

The Power of Probiotics and Prebiotics

Restoring a healthy balance of gut bacteria is crucial. This can be achieved through:

- Probiotics: These are live beneficial bacteria. They can be found in fermented foods like yogurt (unsweetened), kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha. Probiotic supplements containing well-researched strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium can also be beneficial.

- Prebiotics: These are types of fiber that humans can’t digest but serve as food for beneficial gut bacteria. Excellent sources include garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, bananas, and chicory root.

Key Nutrients and Supplements: What Does the Evidence Say?

While a food-first approach is best, certain supplements have shown promise in supporting gut barrier function in clinical studies.

A 2023 review in the journal Foods summarized the evidence:

- L-Glutamine: This amino acid is a critical fuel source for intestinal cells and plays a role in maintaining tight junction integrity. A notable study on post-infectious IBS-D found that glutamine significantly reduced intestinal hyperpermeability and improved symptoms.

- Zinc: This mineral is essential for maintaining the integrity of the gut lining. Zinc carnosine, in particular, has been shown to help protect the gut from damage caused by NSAIDs.

- Vitamin D: Vitamin D plays a key role in immune function and has been shown to help maintain tight junctions and reduce inflammation in the gut.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Found in fatty fish like salmon, these fats have powerful anti-inflammatory properties that can help soothe an inflamed gut.

It is essential to consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new supplement regimen.

Creating Your Leaky Gut Diet Plan: Foods to Eat and Avoid

To simplify the dietary approach, here is a table outlining foods that generally support gut integrity versus those that may compromise it.

This is a general guide, and individual tolerances may vary.

| Foods that Support Gut Integrity (Eat More) | Foods that May Compromise Gut Integrity (Eat Less) |

|---|---|

| Fermented Foods: Sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, plain yogurt, kombucha | Refined Sugars & High Fructose Corn Syrup: Soda, candy, pastries, many processed foods |

| High-Fiber Vegetables: Broccoli, Brussels sprouts, leafy greens, asparagus, artichokes | Processed & Packaged Foods: Fast food, frozen dinners, chips, crackers with additives |

| Root Vegetables: Sweet potatoes, carrots, squash, turnips | Industrial Seed Oils: Soybean, corn, canola, sunflower, safflower oils |

| Low-Sugar Fruits: Berries, avocados, lemons, limes | Excessive Alcohol: Particularly beer and sugary cocktails |

| Healthy Fats: Olive oil, coconut oil, avocados, nuts, seeds | Artificial Sweeteners: Aspartame, sucralose, saccharin (can alter microbiome) |

| Quality Proteins: Wild-caught fish (salmon, sardines), pasture-raised poultry, grass-fed meats | Common Irritants (for some): Gluten-containing grains (wheat, barley, rye), conventional dairy |

| Bone Broth: Rich in collagen, gelatin, and amino acids like glycine and proline | Food Additives: Emulsifiers, carrageenan, artificial colors and flavors |

When Should You See a Doctor?

While dietary and lifestyle changes can be powerful, self-diagnosing and self-treating can be dangerous.

It’s crucial to work with a qualified healthcare professional to rule out more serious conditions and develop a safe and effective treatment plan.

Red Flag Symptoms You Shouldn’t Ignore

If you experience any of the following symptoms, seek medical attention promptly:

- Unexplained weight loss

- Blood in your stool

- Severe abdominal pain

- Persistent fever

- Difficulty swallowing

- Anemia or signs of nutritional deficiencies

These can be signs of serious conditions like IBD, celiac disease, or cancer, which require medical diagnosis and treatment.

How to Talk to Your Doctor About Your Gut Health

Instead of saying “I think I have leaky gut syndrome”, which might be dismissed, try framing the conversation around your specific symptoms and concerns. For example:

“I’ve been experiencing chronic bloating, food sensitivities, and fatigue. I’ve read about the connection between gut health, inflammation, and these kinds of symptoms. I’m concerned about my gut barrier function and would like to explore potential underlying causes. Could we test for conditions like celiac disease or SIBO?”

This approach opens a collaborative dialogue based on recognized medical concepts and demonstrates that you are an informed and engaged patient.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is leaky gut syndrome a real diagnosis?

No, “leaky gut syndrome” is not a formal medical diagnosis. However, the underlying mechanism, increased intestinal permeability, is a real, scientifically recognized phenomenon that is associated with several chronic diseases, particularly autoimmune conditions.

2. Can a blood test diagnose leaky gut?

Currently, there are no validated or reliable blood tests available for clinical use that can diagnose leaky gut. Commercial tests for zonulin or food antibodies are not recommended by most medical experts due to a lack of scientific validation.

3. Does gluten cause leaky gut in everyone?

No. Gluten is a known trigger for increased permeability in individuals with celiac disease and possibly those with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. For the majority of the population without these conditions, moderate gluten consumption does not appear to cause a leaky gut.

4. How long does it take to heal a leaky gut?

There is no set timeline, as it depends on the underlying causes and the consistency of treatment. With a dedicated dietary and lifestyle approach, some people report feeling better within a few weeks, while for others, it may take several months to a year to significantly improve gut barrier function.

5. Are probiotics essential for healing a leaky gut?

While not strictly essential, probiotics from fermented foods and supplements can be highly beneficial. They help restore a healthy balance of gut bacteria (the microbiome), which is a critical component of a strong and resilient gut barrier. Many protocols for healing Leaky Gut Syndrome include a focus on probiotic-rich foods.

6. What is the single best food for gut health?

There is no single “best” food. The key is dietary diversity. However, fiber-rich plant foods (vegetables, fruits, legumes) and fermented foods (like sauerkraut or kefir) are consistently highlighted by research for their powerful benefits on the microbiome and gut lining.

7. Can stress alone cause leaky gut?

Chronic stress is a powerful trigger that can significantly increase intestinal permeability. Through the gut-brain axis, stress hormones can directly impact tight junctions and alter the microbiome, making it a major contributing factor to Leaky Gut Syndrome, even in the absence of a poor diet.

8. Is leaky gut the same as IBS?

They are not the same, but they are related. Increased intestinal permeability is found in a significant subset of people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), especially the diarrhea-predominant type. It is considered one of the potential underlying mechanisms contributing to IBS symptoms.

9. Do I need expensive supplements to fix my gut?

No. The foundation of healing is always diet and lifestyle. While some targeted supplements like L-glutamine or zinc can be helpful, they are not a magic cure for Leaky Gut Syndrome. They should be considered adjuncts to a whole-foods, anti-inflammatory diet, not a replacement for it. Always consult a professional first.

Conclusion

The debate over leaky gut syndrome highlights a crucial shift in medicine: a growing recognition of the gut’s central role in overall health.

While the “syndrome” itself remains a controversial lay term, the science of increased intestinal permeability is robust and revealing.

It is not a fringe theory but a tangible biological process linked to inflammation and a growing list of chronic health conditions.

The key takeaway is not to get bogged down in terminology, but to focus on the actionable principles of gut health.

By removing inflammatory triggers, nourishing your body with whole foods, managing stress, and supporting a diverse microbiome, you can take powerful steps to strengthen your gut barrier.

This approach doesn’t just address a “leaky gut”, it builds the foundation for long-term, vibrant health.

If you are struggling with chronic symptoms, the most important step is to partner with a knowledgeable healthcare provider who will listen to your concerns and help you navigate the path to a proper diagnosis and a healthier gut.